Anti-cybercrime law: It may be harsh to call me a cybercriminal, but the new law says I am

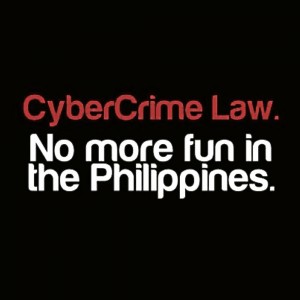

Like the lights on a building going out one by one, I watched my newsfeed on Facebook and Twitter get crowded with black squares as people switched their headers and profile pictures to demonstrate their protest against the anti-cybercrime law.

Like the lights on a building going out one by one, I watched my newsfeed on Facebook and Twitter get crowded with black squares as people switched their headers and profile pictures to demonstrate their protest against the anti-cybercrime law.

A screen capture of an inane question from a senatorial aspirant, on whether the law infringes on the freedom of expression, was immediately trending.

Sen. Tito Sotto, everyone’s favorite punching bag, was immediately at the forefront of the discussion, landing in Forbes. National heroes like José Rizal and Apolinario Mabini were pictured gagged with a censoring black bar. The Internet Armageddon is about to hit Philippine cyberspace.

The anti-cybercrime law received outright condemnation from various sectors in and outside the Philippines. The primary issue against it is the provision on cyberlibel snuck in by Sen. Tito Sotto, who proudly admitted it, and sees nothing wrong with having done so.

A columnist in Forbes magazine said the law, due to the provision on cyberlibel, makes the Stop Online Piracy Act (Sopa) in the US seem reasonable, as the latter only seeks to take down “file-sharing.” International organizations, along with the local human rights watch, had expressed concerns that this is a step backward for the Philippines, which is already behind the international community in decriminalizing libel.

Exception

Under the new law, cyberlibel imposes a penalty of reclusion perpetua, a greater penalty than ordinary libel. Sotto reasoned that if mainstream media are liable for ordinary libel, what is so special with bloggers and users of social media that merits exception to the threat of penalty? He says the law will make the people act more responsibly on cyberspace. He is on a mission to civilize, to single-handedly change the culture on the Internet.

“Yes, I did it. I inserted the provision on libel. Because I believe in it and I don’t think there’s any additional harm.”—Sen. Vicente “Tito” Sotto III (in an article written by Paul Tassi, published in www.forbes.com, Oct. 2).

Statements like this, in the word of the Forbes columnist, only reveals a lack of understanding of how the Internet works. It is saddening because it also shows a disconnect between the upper rung of the power structure in the Philippines and the general populace, particularly with the middle class, who use the Internet to express grievances against the government.

This does a great disservice to the cause. Most people would agree that there is a need to curb the prevalence of cyberbullying. But should it be at the expense of free speech? The problem with the provision on cyberlibel is, it is vague, with enough wiggle room to enable the government to crack down on dissenters.

Internet giant Google, the second most valuable company in the world, decreed, “Democracy works on the Web.” Cyber-space recently showed this in action on Reddit, when a college student posted a photo of a Sikh woman sporting body hair. It immediately received a backlash, and overturned the table in favor of the woman who shared her belief with the users of the social media.

There are studies that show that anonymity on the Internet makes people more mean, because it allows them to escape accountability. Websites, especially news outlets, responded to this problem by installing the service Disqus, which obliges readers to use Facebook and other social media to identify themselves, to allow readers to comment. This has resulted in more intelligible discourses on the web.

There is still the problem of fictitious accounts. But it’s a problem that is nearing a solution, too. Facebook has recently cracked down on fake accounts on their website. The point is, like a free market, the Web has a way of regulating and correcting itself without need for too much interference from the government.

Jeff Jarvis, in his book “What Would Google Do,” documents how netizens use the Internet to express their dissatisfaction with corporation. Jarvis popularly took on hardware maker Dell due to its bad customer service. He subsequently collaborated with the tech giant on how to make their product better. Jarvis continues on this theme, expounding on how the Internet enables “power sharing” between corporations and the ordinary consumer. The concentration of power in corporation is democratized through the Internet—and it works!

This is the same thing that’s happening in the Philippines. Filipinos are the top users of social media websites like Facebook. We have shifted from being the text capital of the world to being the social-media capital of the world. It was only a matter of time when this shift also influenced how we govern ourselves. Filipinos quickly express their grievances against the government on Facebook newsfeed, instead of physically taking it to the parliaments of the streets.

Government leaders and officers were quickly dumbfounded by the instant publicity for their inactions and mistakes. They found themselves in a situation where their power meant nothing. The Internet has shifted control to the Filipinos on Facebook and Twitter.

But there are government leaders who quickly acknowledged this reality. Sen. Pia Cayetano and Sen. Chiz Escudero are among the popular politicians on Twitter, and they engage their followers and address their grievances.

Escudero said the cyberlibel provision was a mistake, while Cayetano admitted, on Twitter, that she missed out on the provision.

New media

President Aquino actively used social media in his 2010 campaign, even installing a New Media group under Leah Navarro of the Black and White Movement. Interestingly, Sotto is inactive on social media.

To be fair to President Aquino, his only course of action is to sign the law or veto it as a whole (line vetoing is only allowed in budget acts). He must have weighed the good and the bad of the law, and found that there is a pressing need to curb evils like child pornography, piracy and hacking, among others. The ball is now with the Supreme Court, and it is up to them to strike down provisions that it deems in conflict with the Constitution. Escudero and Cayetano have already filed an amending bill.

The fiasco over the anti-cybercrime law only goes to show the ability of Internet users to influence government and serve as a platform to counter legislation and policies that are deemed detrimental to the people. Leaders are able to quickly see the clamor for it, and respond. Not only does the Internet make for a participative government; it also compels the government to be more responsive.

My newsfeed is still on a blackout. It makes chatting a little tricky, but it’s a small sacrifice to make to take a stand against the provision on cyberlibel.