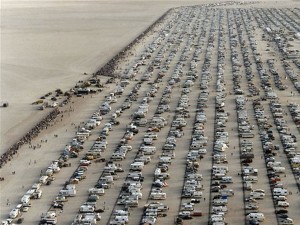

TAILGATE PARTY TIME. NASA 1982 photo shows vehicles parked at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert for a space shuttle landing. NASA estimates a crowd of approximately 500,000 watched the landing from the East Shore public viewing site (AP Photo/NASA).

EDWARDS AIR FORCE BASE, California— If the weather cooperates, Atlantis will close out the space shuttle era with a landing in Florida. Shuttle homecomings didn’t always end this way.

For much of the first decade of the program, Edwards Air Force Base was the go-to landing site, 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) away in California, until shuttles started to routinely land in Cape Canaveral.

In the early days, spectators descended on the Mojave Desert the day before and waited for the shuttle to herald its return from orbit with ear-splitting twin sonic booms.

Overnight, a sea of people would sprout up in the high desert, edging out year-round residents, the Joshua trees and desert tortoises. Trains of RVs fought sedans for the best vantage point. Adults pitched tents and stoked bonfires. Gaggles of kids became a patriotic chorus.

The atmosphere rivalled a rambunctious football tailgate party or rock music festival — only geekier.

“There was way too much energy to sleep,” recalled G. Scott Ellwood, who made the trip from San Diego to watch six landings at Edwards.

The military outpost about 100 miles (160 kilometers) north of Los Angeles boasts a storied past. It was where Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in a flight of the X-1 rocket plane in 1947 and where the 1986 around-the-world flight of Voyager took off and landed.

Edwards was selected because it was home to vast dry lakebeds that were softer, wider and longer than the marsh-surrounded concrete runway at Cape Canaveral on Florida’s coast, where the shuttles lifted off. The spaciousness meant there was plenty of room for error if brakes locked up or tires blew out.

Once astronauts gained experience in landing, Edwards was demoted to backup in case of rain and clouds in Florida — true even to today as NASA prepares to retire the shuttle fleet after three decades.

George Grimshaw, shuttle project manager at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center located on the base, said it was tough to be relegated to second place. But “we were confident we would get our fair share of landings out here just because of the weather,” he said.

Of the 132 shuttle landings, 54 swooped out of the desert sky and glided to a stop on Edwards’ lakebed runway or its 15,000-foot concrete air strip. Seventy-seven returned to Florida. Only one shuttle was diverted to White Sands, New Mexico in 1982 after flooding swamped runways in California and Florida. Two flights — Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003 — ended in tragedies.

Since flights resumed in 2005, there have been only five shuttle landings in California. The last detour occurred on Sept. 11, 2009. NASA prefers Florida because it saves the space agency the headache and expense of a $1.8 million (€1.27 million) cross-country flight to get the shuttle back to its home base.

Atlantis, the 135th and final shuttle mission, is scheduled to land at Cape Canaveral just before sunrise Thursday. As usual, Edwards Air Force Base may get the last-minute call if there’s bad weather.

The base has not yet decided whether to open the public viewing area should Atlantis get diverted. The public space has rarely been open since the base became backup, though die-hards can still steal a peek from the side of the road.

Even if it lands here, it likely won’t be greeted by the spectacle of the early years. The public will not be given much advance notice and the landing would be in morning darkness.

“I understand the desire to come out,” said base spokesman John Haire. “Unquestionably, the best seat in the house will be on TV.”

It was two years after the Challenger launch explosion that Ellwood, who worked on flight simulators in San Diego, decided to caravan north in 1988 with his 3-year-old daughter and two best friends to see the first shuttle landing since the accident.

The quartet arrived the day before to an electric crowd. They struck up conversations with strangers and gawked at aerospace pins and patches for sale. When night fell, generators started humming and music wafted from campsites.

“It was the most exciting tailgate party you’ve ever seen,” said Ellwood, who now lives in Texas.

When Discovery rattled the desert with its trademark sonic booms the next day, the mass of 400,000 cheered then fell silent for several minutes until the wheels touched down.

The collective hush gave Ellwood the goose bumps and a sense of camaraderie. Since that landing, he has seen five other shuttles return to Edwards.

Those with the biggest stake in seeing the shuttle return safely included the workers who rushed out to the tarmac after a landing. When it was a tossup between Florida or California, crews on the West Coast would not know until an hour or so beforehand.

Contractor Phil Burkhardt, who has worked on the shuttle program since 1985, held various jobs. On several landings, he drove the astronauts from the shuttle to get their medical checkups. He was also the shuttle tow guy. He had to make a sweeping U-turn on the concrete runway with the shuttle in tow.

“I kept telling myself, ‘Take it nice and slow. Use every bit of this runway,'” Burkhardt said.

If something happened, “this was a good place to be famous for the wrong thing,” he said.

Once the shuttle program ends, the equipment at Edwards will find a new home or end up on the scrapheap. The most visible item, a hulking structure that mates the shuttle to a jumbo jetliner for the ride to Florida, will be demolished next year after NASA failed to find a buyer.

The shuttle workforce in California is much smaller than Florida and Texas, where thousands face layoffs. Only about 275 people from Edwards and Dryden typically mobilize for a landing. Most of them have other jobs, but about two dozen contractors face an uncertain future.

As for Edwards Air Force Base, it will continue to serve as a place for experimental aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicle testing.

Grimshaw, the shuttle chief at Dryden, is bracing for the program’s close: “It’s sad. It’s hard to believe that something that has been a big part of our lives is actually ending.”