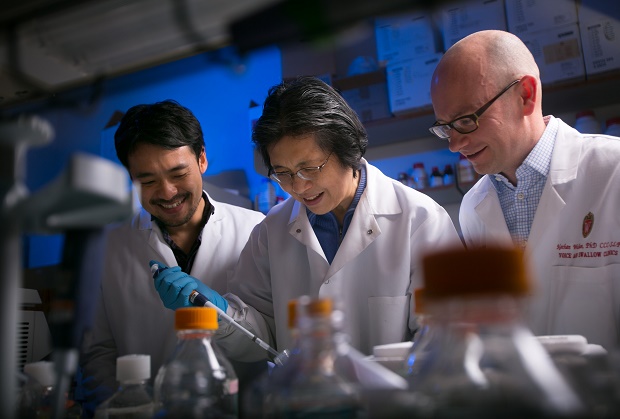

This photo provided by John Maniaci/UW Health, taken Nov. 16, 2015, shows Dr. Nathan Welham, right, visiting scientist Kohei Nishimoto, left, and associate scientist Changying Ling working in the Welham Lab at the Wisconsin Institute for Medical Research in Madison, Wis. Welham and his team have bio-engineered vocal chords that can generate a voice in humans. AP

WASHINGTON — From a mothers comforting croon to a shout of warning, human voices are the main way people we communicate and one taken for granted unless something goes wrong. Now US researchers have grown human vocal cords in the laboratory that appear capable of producing sound — in hopes of one day helping people with voice-robbing diseases or injuries.

Millions of people suffer from voice impairments, usually the temporary kind such as laryngitis from a virus or a singer who overdoes the performing. But sometimes the vocal cords become too scarred and stiff to work properly, or even develop cancer and must be removed. There are few treatments for extensive damage.

Your voice depends on tiny but complex pieces of tissue that must be soft and flexible enough to vibrate as air moves over them — the way they make sound — but tough enough to survive banging together hundreds of times a second.

Wednesday, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison reported the first lab-grown replacement tissue that appears pretty close to the real thing — and that produced some sound when tested in voice boxes taken from animals.

“There is no other tissue in the human body that is subject to these types of biomechanical demands,” said Dr. Nathan Welham of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who led the work published in Science Translational Medicine. “This lends promise or hope to one day treating some of the most severe voice problems that we face.”

The vocal cords, what scientists call “vocal folds,” sit inside the larynx or voice box, near the Adam’s apple in the neck. Welham’s team started with some rare donations of vocal cords from four patients who had had their larynx removed for non-cancerous reasons, and from one deceased donor. The researchers culled two types of cells that made up most of the tissue, and grew a large supply of them.

Then they arranged the cells on 3-D collagen scaffolding, and the two cell types began mixing and growing. In 14 days, the result was tissue with the shape and elasticity of human vocal cords, and with similar chemical properties.

But could it work? To tell, the researchers turned to a technique that sounds, well, strange but is a staple in voice research. They took a larynx that had been removed from a large dog after its death and attached it to a plastic “windpipe” that blew in warm air to simulate breath.

A dog’s voice box is pretty similar to a human’s, Welham said. So the researchers cut out one of the native canine vocal folds and glued a piece of the new bioengineered tissue in its place.

Sure enough, the human tissue vibrated correctly and made sound — a buzzing almost like a kazoo, the recordings show.

It didn’t sound like a voice because it takes all the resonating structures of the mouth, throat and nose to “give the human voice its richness and individuality, and make my voice sound recognizable to my loved ones and you to yours,” Welham explained.

But that raw sound was essentially the same when the researchers tested the unaltered dog larynx and when they substituted the newly grown human tissue, suggesting the sound should be more normal if it were placed inside a body, Welham said.

Wouldn’t the body reject tissue grown from someone else’s cells? Further study using mice engineered to have human immune systems suggested this bioengineered tissue may be tolerated much like corneal transplants, less rejection-prone than other body parts.

This is a first-stage study, and it will take far more research before the approach could be tested in people, cautioned Dr. Norman Hogikyan, a voice specialist at the University of Michigan, who wasn’t involved in the new research.

But “I was impressed,” Hogikyan said. Growing replacement tissue “is an important step that’s potentially useful in treating scarring from a wide range of reasons.”

RELATED STORIES Prosthetic eye maker brings relief to wounded Gazans

Transplant gives new face, scalp to burned firefighter