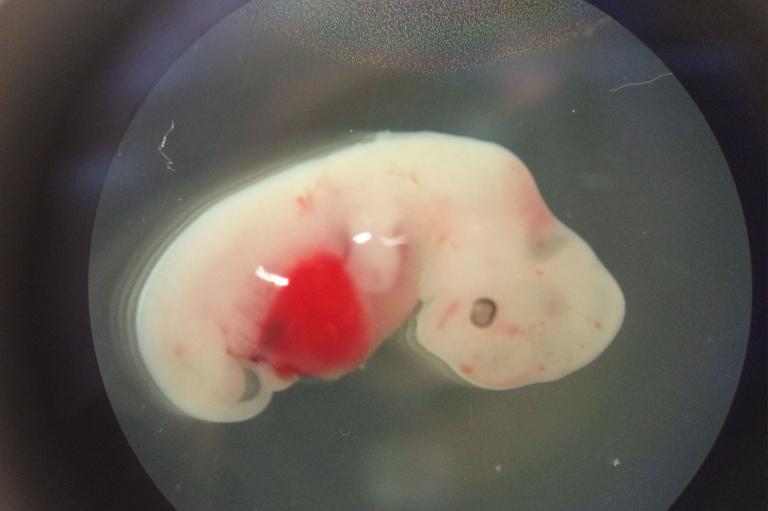

This embryo is one of the many pig embryos inserted with human cells. This one in particular is in its fourth week of development. Image: Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte

Organ transplants are one of the riskiest medical procedures one can undergo. Apart from the difficulty of looking for donor organs, it can be dangerous when the organ recipient’s body rejects the donated organ. This is why scientists continue to research ways of artificially growing donor organs.

Now the research has taken a big step forward.

National Geographic reports that a team of scientists is currently studying how to grow donor organs in pigs that have human cells. The pig where the lung will come from can be scientifically classified as a chimera – an organism that has cells from two different species.

The scientists hope that by creating human-pig chimera embryos, they may be able to grow donor organs that have a lesser risk of rejection in humans, due to the human cells present in the chimera organs.

Research was difficult. The team lead by Jun Wu of the Salk Institute had to piggy-back their study on previous work that involved mice and rats. Rat cells were inserted into mice embryos.

The reason why the scientists chose pigs as a leap-off point for this study is due to the large similarities of pig and human organs.

For their experiments, the Salk research team is currently utilizing a genome editing tool called CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) to essentially hack the pig organs and attempt to get rid of viruses that might be harmful to humans.

Human-animal chimeras are a bit of a sensitive subject, which is why researching them is difficult. First, experiments regarding this topic is ineligible for public funding in the United States. The Salk team has to rely on private donors to pursue their studies. Second, public opinion is not exactly fond of the idea of organisms that are part human, part animal.

As of now, chimera donor organs are still not viable because there is still too little amount of human tissue that can be inserted into pig embryos. Apparently, human cells tend to slow the growth of embryos.

Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in the SAlk Institute’s Gene Expression Laboratory notes that it could take years to create functioning human organs using this process. On the other hand, the technique they used for this study could also be applied on the study of human embryo development.

Stem cell expert Ke Cheng from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University calls the study a breakthrough. “There are other steps to take,” he concedes. “But it’s intriguing. Very intriguing.” Alfred Bayle