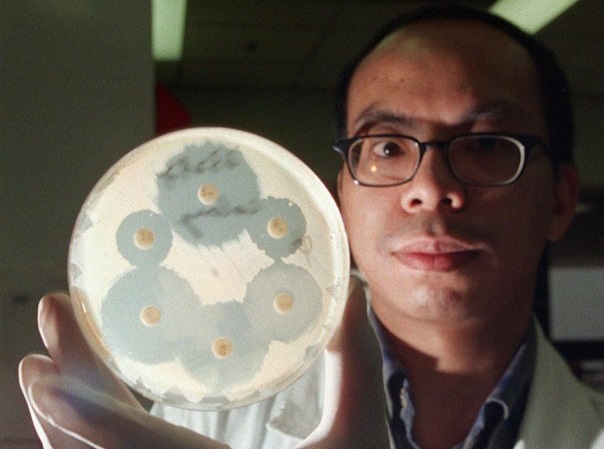

Ho Po-on, a medical technologist at Queen Mary hospital, Hong Kong, holds a drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus culture, a new superbug that has killed one person in Hong Kong. Medical experts here are to hold urgent talks on how to fight the vancomycin-resistant bacteria. AFP

PARIS, France — The UN’s health agency urged governments, scientists and pharma companies Monday to create new drugs to tackle 12 antibiotics-resistant supergerms threatening an explosion of incurable disease.

For the first time, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a list of bacteria threatening to turn once easily-treatable infections into serial killers.

“Antibiotic resistance is growing, and we are fast running out of treatment options,” said Marie-Paule Kieny, assistant director-general of the WHO, which previously warned the world may be headed for a “post-antibiotic” era.

“If we leave it to market forces alone, the new antibiotics we most urgently need are not going to be developed in time.”

READ: US woman dies of infection resistant to all 26 available antibiotics | Antibiotic resistance is becoming a serious concern

The agency listed 12 groups of bacteria that no longer respond to an ever-growing list of ineffective antibiotics.

The germs cause ailments including lung, blood, brain, and urinary tract infections, food poisoning from salmonella and sexually-transmitted gonorrhea.

Bacteria can become resistant to drugs when people take incorrect doses of antibiotics. Resistant strains can also be contracted directly from animals, water and air, or other people.

When the most common antibiotics fail to work, more expensive types must be tried, resulting in longer illness and treatment, often in hospital. Increasingly, cases are reported in which no existing drug works.

The 12 bacteria types targeted by the WHO were prioritized based on the severity of disease they cause, how easily they spread, how many drugs still work against them and how many new ones are already being developed.

“Why do we need such a list? Well, until about 30 years ago the world was seeing tens of new antibiotics being approved and coming to market,” Kieny told a telephone press briefing.

“But today, when resistance to antibiotics is reaching alarming proportions, the pipeline is practically dry.”

Spend now, save later

The reasons, Kieny said, included a lack of market incentives compared to treatments for chronic diseases, for example, which deliver a much higher return on investment.

The list was meant to encourage governments to adopt policies and incentives to boost drug research and development by public and private entities, said Kieny.

If they invest now, she added, governments will need to spend less later “when resistance to antibiotics develops into an even deeper crisis.”

The WHO divided its 12 “priority pathogens” into three categories of new medicine priority: critical, high and medium.

The most urgent section contained three bacteria families resistant to carbapenem antibiotics — a last-resort treatment for many life-threatening infections which spread mainly in hospitals among transplant recipients, chemotherapy patients and people in intensive care.

In January, an American woman died of an infection — resistant to all the available antibiotics — caused by a germ called Enterobacteriaceae on the WHO’s critical list.

The “high” and “medium” priority categories include drug-resistant bacteria that cause “more common” diseases such as gonorrhea and salmonella-induced food poisoning which hit poor countries particularly hard, said the WHO.

Doctors Without Borders (MSF), which provides patient care in low-income and war-torn countries, agreed there was a critical need for new drugs.

“We see — with alarming regularity — the critical-listed bacterial infections in people we treat in our field programs, including babies and children, burns victims and conflict and trauma injuries,” said Rupa Kanapathipillai, the body’s adviser on antimicrobial resistance.

Tuberculosis was not on the list because well-funded programs already exist to develop new antibiotics, said the WHO. CBB