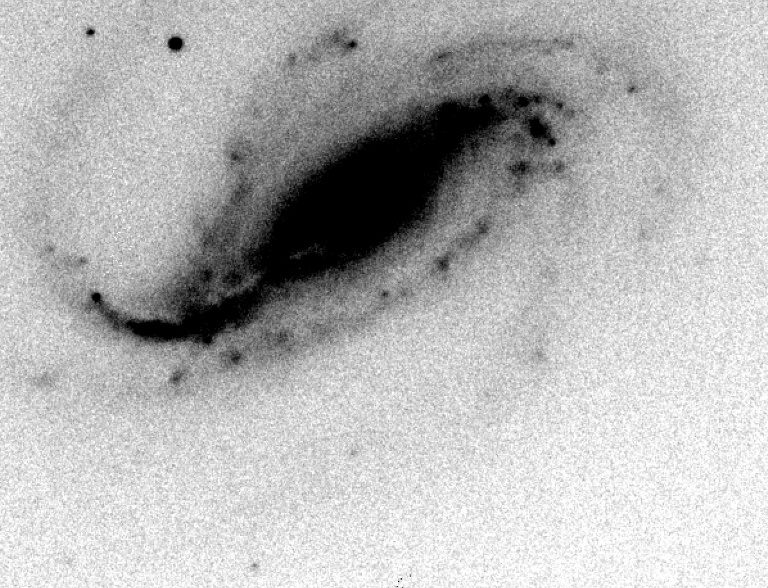

A superimposed series of images captured by an amateur astronomer as a star explodes in a brilliant flash of light and morphs into a supernova. Image: AFP/Victor Buso; Gaston Folatelli

To say that Victor Buso was in the right place at the right time may be the biggest understatement in the history of stargazing.

By pure luck, the amateur astronomer from Rosario, Argentina snapped the first before-and-after images ever captured of a star as it explodes in a brilliant flash of light and morphs into a supernova.

Astronomers call this pivotal moment “shock breakout”, and have dreamt for decades of witnessing such a stellar metamorphosis in real time.

Melina Bersten, a scientist at the La Plata Astrophysics Institute in Argentina and lead author of a study in journal Nature that describes the discovery, put the odds of stumbling across it at up to 1 in 100 million.

“It’s like winning the cosmic lottery,” quipped co-author Alex Filippenko, an astronomer at the University of California Berkeley.

In September 2016, Buso was testing a new camera on his 16-inch telescope when he noticed a bright flash from the southern constellation Sculptor on one of the images.

The galaxy hosting the star is about 80 million light years away, which is also the time it took for the light cast by the explosion to reach Earth.

Buso knew enough to contact Bersten, who instantly realized that the weekend stargazer had found a diamond in the rough.

She put out the word to an international group of astronomers, and within hours big-league telescopes around the world were trained on SN 2016gkg, the name given to the newly baptized supernova.

“Professional stargazers have long been searching for such an event,” said Filippenko, who followed up from the Lick Observatory near San Jose, California.

Reality checks

“Observations of stars in the first moments they begin exploding provide information that cannot be directly obtained in any other way.”

The new data provide key clues, for example, about the physical structure of the star just before its catastrophic demise, as well as the nature of the explosion itself.

It was also an opportunity for scientists to conduct reality checks.

“For the first time, this fortuitous discovery allows astronomers to test the validity of their models on real data,” co-author Federico Garcia, an astrophysicist at Paris Diderot University, told AFP.

“It was a great feeling when I saw the images,” he added.

Analysis of the event showed that the SN 2016gkg is a Type IIb supernova, emerging from a massive star that has lost most of its hydrogen envelop before it explodes.

This category of supernova was first identified by Filippenko in 1987.

Combining data with theoretical models, the team estimated that the initial mass of the star was about 20 times great that the mass of our Sun.

By the time it detonated, however, it had lost three-quarters of that mass, probably sucked away by a companion star.

The unfolding drama was also observed with the twin 10-metre telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaii. CC

RELATED STORY:

Stellar encore: Dying star keeps coming back big time