You cross paths in cyberspace. You click, literally and figuratively, and romance starts instantly.

For months, you’re in a web of bliss until something happens: The significant other meets an accident, gets into trouble with the law, or falls ill.

Out of concern and affection, you offer to pay for some of the expenses.

The cybermate accepts, though with seeming hesitation, but asks, for some reason, that the cash be deposited in the bank account of a relative or a friend, or sent through money transfer.

You send a message that the cash has been sent, but no response.

Then you notice that your lover’s social media account has been deleted and that she or he can’t be reached by phone.

Everything’s gone, like your online love affair never existed.

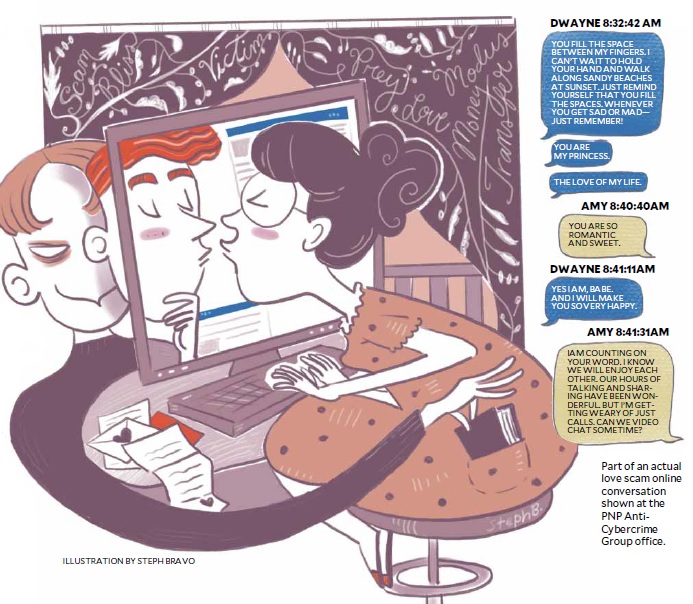

That scenario is typical of the “love scam” in which “willing victims” lose hundreds of thousands or, sometimes, even millions of pesos to imaginary lovers on the internet, according to the Philippine National Police Anti-Cybercrime Group (PNP-ACG).

The PNP-ACG spokesperson, Senior Insp. Artemio Cinco Jr., said 10 percent of internet fraud reported in the country in 2017 fell under the love or romance scam category.

“This is a financial fraud case because the love scam is motivated by money. The suspect has someone fall in love [with] and enter into an online relationship until such time that the victim releases a certain amount of cash,” Cinco said.

There are different styles used, “but basically what those behind it will do is get your trust and affection,” Cinco said.

Below are some of the stories of victims, whose names the Inquirer replaced with pseudonyms.

Rita’s case

Rita met Chuck online. He told her he was an American soldier assigned to Afghanistan. He became her cyberboyfriend.

Chuck claimed that in one military operation, his team recovered several boxes of US dollars which they could not take to the United States from Afghanistan. He, instead, sent the boxes to her.

Rita later received a call from a man who identified himself as a customs officer and told her that she must pay P150,000 for the package.

She paid the amount after Chuck assured her that the money he had sent was more than enough to cover her expenses.

More calls from the customs officer followed, asking her to pay P500,000. The amount ballooned to over P1 million.

Finally, she was told to pick up the boxes at Ninoy Aquino International Airport, where she realized she had been duped.

Helen’s case

In 2016, Helen met Roger on Facebook. Roger said he was a British widower and a chemical engineer.

They later shifted their chats to Viber and soon their cyberromance started.

Roger later confided to Helen that he needed money to get work documents in Malaysia. He claimed that his credit card could not be activated in that country and that he could not access his British bank account because of a system glitch.

Helen sent him P340,000 through money transfer after he promised to pay her back — with interest — on his visit to Manila on May 3, 2016.

On that day, however, she received a call from a woman who informed her that her boyfriend had an accident and needed money to pay his medical bills.

She sent more than P200,000, again via money transfer.

When Roger said he was well enough to travel to Manila, Malaysian immigration officials supposedly detained him at the airport because of his “unpaid liabilities” to the Malaysian company amounting to $10,000.

She received a picture purportedly showing him in immigration custody.

The woman who had told her about his “accident” again called to ask for money so he could be released and fly to Manila.

By then, Helen realized that she was being swindled and filed a complaint in the PNP-ACG.

Pete’s case

Pete, a Filipino-American, met Rosa on a dating website in May last year, and began to exchange emails with her so he could know her better.

A month later, she supposedly suffered a mouth injury in an accident.

“I offered to send her funds for dental attention. She ‘reluctantly’ accepted,” Pete said.

His first money transfer to her was made in late July that Rosa described as “an act of love,” which he did a second time after she told him that she had lost her home in a flood.

In August, Rosa proposed that they acquire an apartment for rent to female bedspacers. He agreed and sent money for it.

After she told him that the apartment had been set up, he asked for documents, receipts and pictures of the place and its tenants.

“But she began to deflect these requests with excuses which sounded reasonable at the time,” Pete said.

After a month, he became suspicious and investigated.

He found that the picture Rosa had used in the dating website appeared in other social media sites but under different names.

When Pete confronted her about it, Rosa said she was using “business pseudonyms.”

Later, she said her identity must have been stolen, and eventually, she stopped contacting him.

By then, Pete had lost P800,000 to her.

It is difficult to tell how widespread in the Philippines the scam is.

The five-year-old PNP-ACG does not have town-level presence, only regional offices, and victims hesitate to travel long distances to file a complaint.

Ashamed

In most cases, the complainants do not make a report. They are too ashamed “to admit to being a victim of the love scam,” Cinco said.

He said most of the victims were picked at random from a vast online pool by cyberlotharios “looking for an opportunity, which the victims themselves provide.”

The victims open themselves to the scam by accepting invitations from strangers on the internet and sharing personal details with them.

Once hooked, the prey is kept in play by a con artist pretending — as the situation demands — to be a bachelor, a widower or a pretty woman looking for someone “normal” to chat with.

PNP-ACG records show that the usual modus operandi is to entice the victim with a promise of rewards in the form of goods or money, apart from romance.

The delivery of goods, unfortunately, always hits a snag when the scammer, who usually poses as a foreigner, asks for help from the victim to supposedly clear the package from customs.

In a such a situation, a person who identifies himself as a “customs officer” would call the victim to say that the total value of the shipment is actually multiple times more than the amount declared.

Before the package is released, the victim is told to pay supposed fees and taxes by money transfers or deposits in a bank account.

Often, the victim does not bother to check because of the scammer’s guarantees that the package will arrive, Cinco said.

After the money is sent, the scammer usually disappears. There have been cases, however, where the virtual Valentino perpetrates a series of cons, Cinco said.