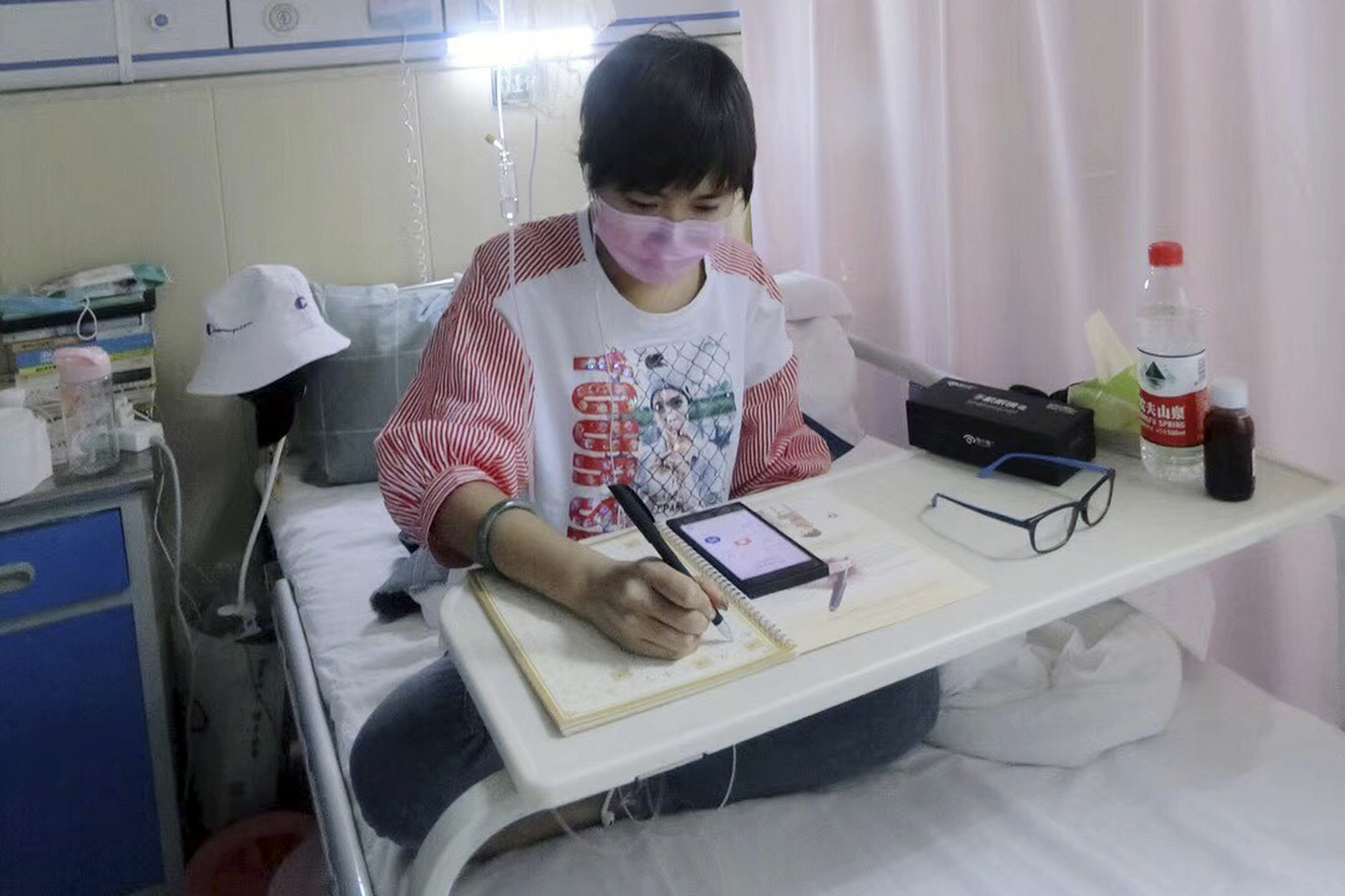

This May 2018 photo released by Su Lingmin shows her with a mask at her hospital bed in Harbin in northeastern China’s Heilongjiang province. Diagnosed with leukemia four months ago, the 27-year-old native of Harbin is helping give a human face to the struggle for more affordable cancer drugs in China. AP

BEIJING, China — At least once a week, Su Lingmin films herself singing, sharing health tips and chatting with hundreds of fans from her hospital bed.

“Now I’m a professional livestreamer,” she said with a smile in a video last week. “What else can I do?”

Diagnosed with leukemia four months ago, the 27-year-old native of the northern Chinese city of Harbin is helping give a human face to the struggle for more affordable cancer drugs in China.

That cause has been bolstered by the popularity of a recent film, “Dying to Survive,” which follows the darkly comedic capers of a Chinese businessman-turned-drug smuggler who saves lives by illegally importing a leukemia drug from India, where it costs several times less than in China.

Inspired by a true story, the movie has made more than $400 million since its release in early July, winning praise from moviegoers and critics and prompting government action.

State news agency Xinhua reported last week that several provinces have lowered drug prices by up to 10 percent since the end of June. Most of the drugs targeted for price reductions are imported, like the Swiss-developed Gleevec medication in “Dying to Survive.”

Beijing previously announced in May that cancer drugs would be exempt from import tariffs. Chinese labs are said to be designing equally effective drugs for a fraction of the price, Xinhua said.

“Imported drugs are just too expensive,” said Du Yanan of the Beijing-based Heart to Heart foundation. Du runs a program that matches each yuan ($0.14) that leukemia patients spend on a form of Gleevec that costs 10,000 yuan ($1,474) for a single box of pills.

Commenting on the discussions sparked by the film, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang vowed to accelerate the process of making cancer medication more affordable.

“At the moment when there is a single cancer patient at home, the whole family must pour out all its resources,” the premier acknowledged.

Some have criticized “Dying to Survive” for vilifying the foreign pharmaceutical company behind the expensive drugs while absolving Chinese authorities of responsibility. But such a portrayal may be necessary to accomplish the unusual feat of at once being critical and assuaging censors, said prominent social commentator Shi Shusi.

“Dying to Survive” was able to “walk the thin tightrope of the regulators’ tolerance” because it addressed serious issues in an indirect, at times slapstick form, Shi said.

“Capitalists have held our moral values for ransom in modern Chinese society,” Shi said. “But this movie shows the desire of Chinese audiences for high-quality art.”

For Su, the leukemia patient in Harbin, the movie spelled out her experience with cancer when one character intoned, “There is only one disease in this world — the disease of being poor.”

On her livestreams, Su sometimes wears a surgical mask. Often, her broadcasts are interrupted by a nurse or doctor who has come to check her blood levels.

She thought at first that she was just stricken with the common cold. One night, she was walking home from a noodle restaurant when she suddenly felt dizzy. By the time she reached her apartment just a few blocks away, she was so weak that her cousin had to carry her to their sixth-floor unit.

Then came the diagnosis, which her parents had at first attempted to hide. They were an “average family,” Su said, with a stable income from her father’s salary as a public servant.

But it was not enough to cover her treatment for the next five years — the length of time her doctor estimated it would take for the cancer to be removed from her system — even when they had already sold their house and spent nearly 400,000 yuan ($58,979) in the last four months.

So Su downloaded Inke, a popular Chinese livestreaming app, and started making videos about life with leukemia. After six weeks, she had nearly 800 fans — enough to make up to 400 yuan ($60) at a time from the virtual gifts her viewers sent her.

The meager earnings were not yet enough to make a real dent in her medical bills, Su said, but livestreaming boosted her confidence and staved off the loneliness of being stuck in a hospital room.

“I am sick, but I’m happy,” Su often tells her viewers. “I know I can be cured.” /cbb