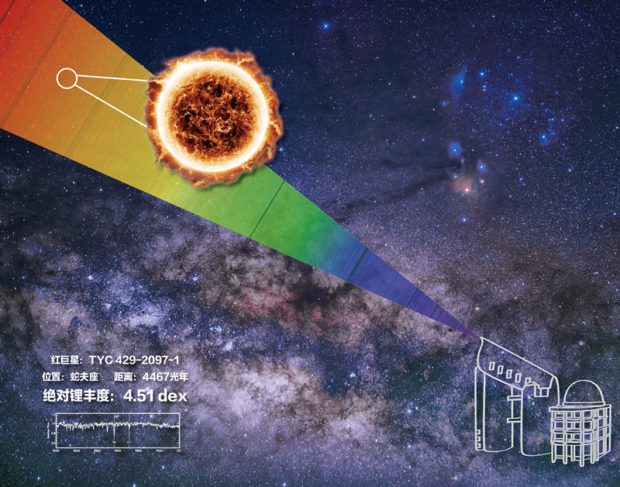

An artist’s design of the extremely lithium-rich star. Photo from Chinese National Astronomy magazine via China Daily/Asia News Network

BEIJING — Chinese astronomers have discovered the most lithium-rich red giant star known in our Milky Way to date. Scientists said on Tuesday that this “extremely rare and interesting” star can help solve the mysteries of stellar evolution and the origin of lithium in our home galaxy.

The newly found giant star is called TYC429-2097-1, and it has 3,000 times more lithium than normal giants. The star, which has 1.5 times the mass and 15 times the radius of our sun, lies in the direction of the constellation Ophiuchus on the north side of the galactic disk, around 4,500 light years from Earth.

Scientists made the discovery using the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope located at the Xinglong Observatory of the National Astronomical Observatories of China in Hebei province. The telescope, which began operating in 2012, is the world’s first optical telescope capable of observing 4,000 stars at once.

After the discovery, scientists conducted a follow-up observation using the Automated Planet Finder telescope at the United States’ Lick Observatory to study this star. The mechanism behind the star’s unusual property was published online on Monday in the science journal Nature Astronomy.

Zhao Gang, director of the operation and development center for LAMOST, said the discovery is another example of China contributing to groundbreaking basic research through its scientific equipment and global collaboration.

“The discovery has drastically increased the upper limit of observable lithium content in stars,” Zhao said. “It also provided a possible explanation for extremely lithium-rich stars and refreshed our understanding of lithium formation in the universe,” Zhao said.

Lithium is the third-lightest element after hydrogen and helium on the periodic table. It is widely used in manufacturing, energy and defense for also being the lightest metal, said Yan Hongliang, an assistant researcher at the National Astronomical Observatories and one of the lead scientists behind the discovery.

Scientists believed hydrogen, helium and lithium were synthesized at the birth of the universe. However, lithium is rare and fragile, so it typically exists in gas clouds of ancient stars.

The lithium caught within stars often is “digested” as stars expand during their dying phase, thus making the element extremely difficult to trace on the stars’ surface, Yan said.

Only 150 lithium-rich giants have been discovered in the past four decades, and just three had the same magnitude of lithium content as the most recent one. “These giants are some of the most challenging and fascinating subjects of study in modern astrophysics,” he said.

Li Haining, an associate researcher at the national observatories, said the older and stranger the star, the better it can reflect the bizarre properties of the early universe. “These special, ancient stars can help us understand the evolution history of stars and possibly the earliest times of the universe,” she said.

During its six years of surveying the sky, LAMOST has also discovered five extremely rare hypervelocity stars that are so fast not even the gravitational pull of the galaxy can stop them from escaping. Only two dozen such stars have been discovered, said Zhao.

LAMOST recently helped measure our home galaxy’s diameter to be 200,000 light years across. A light year is how far light can travel in one year. This is much greater than past estimates, which ranged from 100,000 to 130,000 light years, he said.

In June, LAMOST also launched the world’s largest databank of stellar spectra — light wavelength readings that can reveal information about stars’ velocity, temperature, luminosity and size.