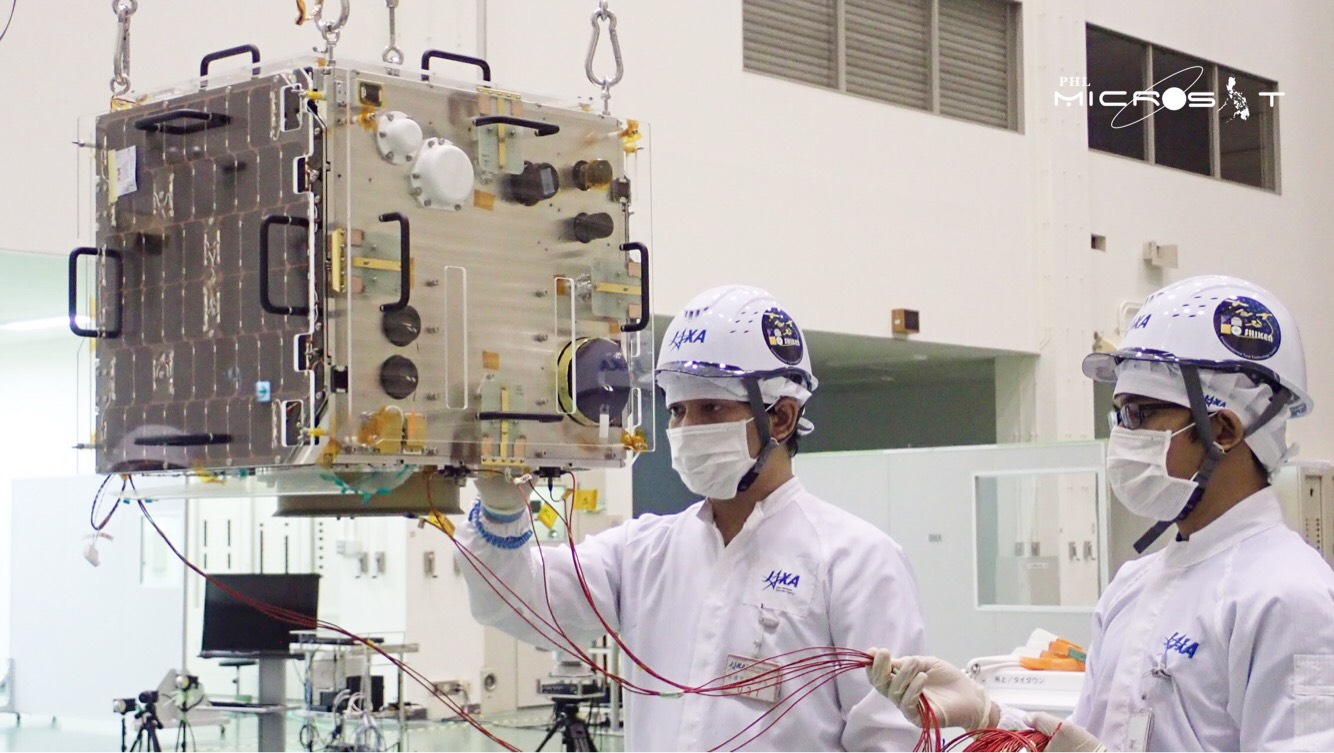

The Diwata-2 flight model was handed over to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency on Aug. 30.

(Updated 7:24 p.m.)

The country successfully sent its second microsatellite, Diwata-2, into space today, just two years after it launched its first ever-satellite, Diwata-1.

The public watching the live stream of the launch at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City erupted into cheers after Diwata-2 has been successfully launched at exactly 12:08 p.m. (Manila time).

The new satellite hitched a ride with an H-IIA F4 rocket of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries from the Tanegashima Space Center of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. It separated from the rocket and started orbiting from space at 12:51 p.m.

Diwata-2 is expected to continue the work of Diwata-1, including determining the extent of damage from disasters, monitoring natural and cultural heritage sites, monitoring changes in vegetation, and observing cloud patterns and weather disturbances.

After more than two years in space, Diwata-1 will reach the end of its life this coming November.

“Nervousness was an understatement on what we felt during the launch,” said Dr. Gay Jane Perez, one of the five project leaders of Philippine Scientific Earth Observation Microsatellite (PHL-Microsat).

The P900-million program, which aims to build, launch, and utilize microsatellites in three years — is a collaboration among the Department of Science and Technology, the University of the Philippines – Diliman, and two Japanese universities — Hokkaido University and Tohoku University.

“We were very afraid because unlike Diwata-1, Diwata-2 was launched straight into space,” she added. “There’s always the possibility that the rocket may explode along with it, or it would not detach and fall back to earth with the projectile.”

Diwata-2, however, will be an improved version of its elder sibling, according to the members of PHL-Microsat.

The Diwata-2 flight model was handed over to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency on Aug. 30.

It weighs 57 kilos and will carry the same four cameras of its predecessor — high-precision telescope, spaceborne multispectral imager with liquid crystal tunable filter, wide field camera, and middle field camera — but will produce sharper images because of a new enhanced resolution camera, according to Dr. Marc Caesar Talampas, a project leader of PHL Microsat.

In addition, Diwata-2 carries experimental modules which were designed and assembled by Filipino scientists and engineers of UPD, with the help of local industries.

There’s also an amateur radio unit which can broadcast a repeating message in times of emergency such as when communication satellites were downed after calamities; and a sun-aspect sensor and experimental attitude control unit, which will help in pointing the cameras to their target location.

Diwata-2 also now has wings, literally, which are deployable solar panels that will power up the additional features of the microsatellite.

Talampas said Diwata-2 will also be staying longer in space at around three to five years, as it will be launched higher at 621 kilometers in a sun-synchronous orbit.

Diwata-1 was launched from the International Space Station in April 2016 at a 420-km low Earth orbit, where satellites naturally experience quicker orbital decay and altitude loss.

Unlike Diwata-1, which has irregular interval of its passes on a specific spot, the sun-synchronous orbit of Diwata-2 allows it to return to the same spot and take its images in a more periodic way, Perez said.

“This will give us an on-demand, post-disaster assessment on the extent of damage brought by a disaster, as well as review the recovery efforts made over time. This will also be helpful in environment monitoring, particularly on the water quality of our inland and coastal waters,” she added. “Ultimately Diwata-2 can help policymakers make right decisions and actions based on the data we have gathered and assessed.”

Models of Diwata-2 (front) and Diwata-1. The second Diwata is an improved version of her elder sister, equipped with solar panel wings, an amateur radio unit and enhanced camera.

Diwata-2 was previously slated to be launched in the second quarter of this year. Asked what caused the delay, PHL-Microsat member Ariston Gonzalez said the delay was on the launching part where “we have not that much of control.”

“On our side, on developing the microsatellite, we are prepared to meet the deadline,” said Gonzalez, one of the nine original engineers of Diwata-1.

He explained: “We have preferences, but they were limited on the altitude and type of orbit for the launching, as well as there are only a number of launching-capable countries. And in the end we chose Japan. But we should also consider that we are not the main passengers of the rocket. So if there’s delay on their part, we have to wait until they were resolved. Only when they’re ready to launch can we share a ride with them.”

The H-IIA rocket’s main loads are KhalifaSat, the United Arab Emirates’s first locally built satellite, and GoSat-2, a greenhouse gases observing satellite of Japan.

Compared with their experience with Diwata-1, when they were building something from scratch with bare knowledge about it, working with Diwata-2 was “smooth sailing,” according to Perez.

“We work with almost the same team; but we have additional people. It is easier in terms of interactions and getting things done because it is already an established project,” she said.

The engineers and scientists of PHL-Microsat, however, said they had a “a self-imposed challenge to raise the bar further.”

“Although we learned something from our Diwata-1 experience, we did not just replicate something we have done already. We wanted to incorporate new items, while minimizing the risk of failure of the whole system,” said Harold Bryan Paler, who is also a pioneering engineer of Diwata-1.

Once they perfected the knowledge and the craft, that’s the time they will venture to build a satellite for the Philippines.

After the launch, a team at the ground receiving station (nicknamed Pedro, or Philippine Earth Data Resource and Observation Center) will establish contact with Diwata-2. Checks and recalibrations will be done until it could be fully operational after one to three months.

Electronics inside Diwata-2 were developed and tested in the Philippines by Filipino engineers. The Filipino craftsmanship was marked by the Philippine flag, the baybayin translation of “Diwata” and the names of the PHL-Microsat members.

Even if it’s not as special as the first time, the people of PHL-Microsat believe that Diwata-2’s launching is also a reason for celebration.

“It’s not everyday that we launch something into space, especially if it is built by Filipinos for the Filipinos,” Perez noted.

“It is a very rare opportunity and experience that people around the world will witness whatt we are capable to do and what used to be just a dream. I also hope this will increase the awareness of our countrymen about space science and technology.”

Perez admitted that space technology is “highfallutin” and even “distant” for the common folk. “What we’re doing does not immediately translate to an effect that will directly impact the people, than say distribute P100 million to every family to buy food or load for their phones. It may be complicated in the first look.”

She went on: “We are not politicians who will promise you this and that. But as scientists and engineers, ultimately at the back of our minds, these things we develop will be useful for the Filipinos — para sa bayan — in response to their needs.” /lb