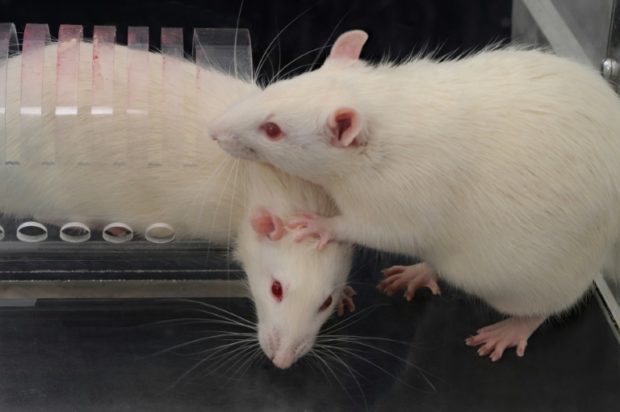

A rat trapped in a restrainer as a free rat opens the restrainer door to liberate the trapped rat. Image: AFP/University of Chicago/David Christopher

Rats are less likely to assist a fellow rodent in need if other members of their group are being unhelpful, according to a study that sheds new light on the so-called “bystander effect.”

Peggy Mason, a neurobiologist at the University of Chicago and the senior author, told AFP the findings helped explain certain human behaviors such as why police officers fail to intervene when one of their own is engaging in brutality.

In an experiment published in Science Advances on Wednesday, scientists found that when a rat encountered a distressed peer in a restrainer, they were generally interested in opening a door and rescuing them.

One or two bystanders, who were rendered unhelpful by giving them a low dose of the anti-anxiety drug midazolam, were then added to the scenario.

In the presence of these unhelpful bystanders, a rat that had previously been helpful in a one-on-one interaction now stood by idly and did not rescue the subject.

On the other hand, when undrugged, helpful bystanders were placed at the scene, a rat that had been helpful one-on-one became even keener on being a good Samaritan.

“I think this is a very apt study for the times,” said Mason, pointing to how during recent United States protests against police racism, protesters rushed to aid injured peers while police stood by.

“In the George Floyd case, there were three other police officers, including one who went into the police force to change the narrative about police brutality against black people — and nonetheless, he stood by and did not intervene,” she added.

Mason likened these officers to the drugged rats, “except they didn’t take the chill pill, they took years of training.”

If a person does not help, “that individual is less likely to be a bad apple and more likely to just be an apple in the orchard, the orchard of mammalian behavior. This is what we do.”

Paradigm shift

The term “bystander effect” was first coined by psychologists after the 1964 murder of Catherine “Kitty” Genovese in New York, whose death was reportedly witnessed by more than 35 of her neighbors, none of whom intervened.

The story was later found to be highly misleading — but the basic finding held up in controlled experiments where human subjects were placed in distressing situations, such as smoke entering the room or a person having a seizure.

When bystanders were added to these scenarios, members of the public who weren’t a part of the experiment often failed to respond.

This led psychologists to hypothesize that perhaps people weren’t willing to take responsibility when others were present.

Mason said the hypothesis suffered from a fatal flaw — the fact that the “bystanders” were in on the experiment and were acting indifferently on purpose.

A study led by Richard Philpot and published in American Psychologist last year in fact found that in the real world, bystanders rarely stood by.

This paper reviewed more than 200 violent incidents recorded on surveillance cameras and showed that people intervened nine times out of 10.

Mason said her paper built on Philpot’s by showing that having helpful bystanders enhanced the desire to help, compared to when there was no audience watching.

On the other hand, having passive spectators decreased the impulse to assist, which reinforces what psychologists found in their early experiments decades ago.

Mason’s team believes that in humans, as for rats, the decision to help or not is more likely linked to the brain’s internal reward circuitry than it is to notions of who should be responsible. IB

RELATED STORIES:

Monkeys infected with novel coronavirus developed short-term immunity

Fossil of giant 70-million-year-old fish found in Argentina