Drones in rice farming: Big gains, big risks

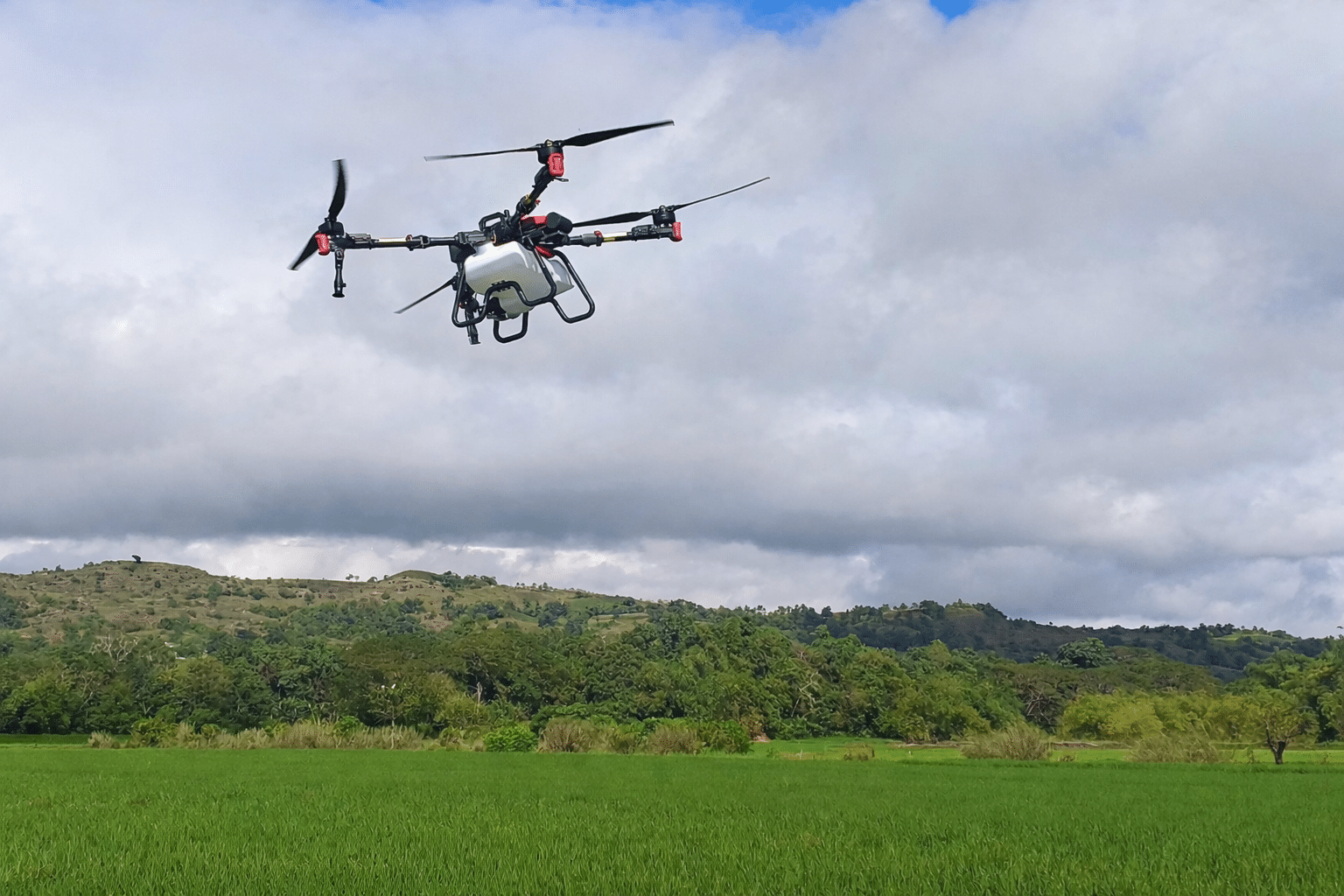

The Philippine Rice Research Institute’s Drones4Rice initiative is pushing rice production deeper into digital agriculture, using drones to automate seeding, spraying, and fertilizer application — a shift supporters say can cut labor costs and improve precision, but one assessment warns could also displace hundreds of thousands of rural jobs and create long-term “hidden costs” tied to soil degradation.

In an ex ante impact assessment of the program, retired University of the Philippines Los Baños professor and agricultural scientist Dr. Teodoro C. Mendoza said scaling drone seeding and spraying to half of the country’s rice areas could displace an estimated 460,000 to 540,000 rural jobs, with annual wage income losses of about P27.5 billion. He also projected that 20 to 25 provinces would face significant employment displacement under that scenario.

Rice, the Philippines’ staple food, is harvested on more than 4.8 million hectares each year, making it a key barometer of food security. The Drones4Rice program, led by PhilRice in collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute and AgriDOM, aims to modernize rice farming by deploying XAG drones for wet direct seeding, pesticide spraying, and fertilizer spreading.

Mendoza’s paper, “Drones4Rice and the Future of Philippine Rice Farming : A Comprehensive Ex Ante Impact Assessment”, argued that the promise of efficiency gains must be weighed against ecological sustainability, rural employment impacts, farmer empowerment, and long-term financial viability.

What Drones4Rice is designed to do

The farming technology includes drone wet direct seeding for inbred and hybrid rice, drone spraying of fungicides and insecticides, and drone spreading of fertilizers. It also covers uniformity testing to check the consistency of seeding and spraying, variable-rate application for fertilizers, and demonstrations and training meant to support adoption.

Mendoza, science director of the nonprofit Community Legal Help & Public Interest Center, described these components as a package intended to improve speed and precision in field operations. But he also said each element carries risks that require safeguards, particularly if drone use accelerates a shift toward direct-seeded rice systems that depend heavily on chemical weed control.

Ex ante assessment framework

Mendoza used an ex ante impact assessment approach — a forward-looking evaluation conducted before full-scale implementation — to project likely effects across ecological, economic and social, financial, health and sustainability dimensions. Unlike ex post assessments that measure outcomes after implementation, ex ante assessments use models, scenarios and projections to estimate potential impacts and guide decision-making.

The quantitative scenario in the paper modeled rural employment impacts if drone seeding and spraying were scaled to 50% of the Philippines’ rice area, or about 2.4 million hectares.

Jobs at risk under a 50% adoption scenario

Under the scenario, Mendoza compared labor requirements for traditional transplanting against drone seeding:

- Traditional transplanting was estimated at 25 to 30 person-days per hectare.

- Drone seeding was estimated at 2 to 3 person-days per hectare for supervision and calibration.

Applied to 2.4 million hectares, the paper estimated traditional practice would require about 60 million to 72 million person-days, while drone adoption would require about 4.8 million to 7.2 million person-days. The difference — about 55 million to 65 million person-days — was presented as labor displacement.

Mendoza translated that gap into an estimated 460,000 to 540,000 rural jobs displaced. Using an assumed P500 daily wage, the paper estimated wage income losses of about P27.5 billion annually.

Rice is grown in 46 of the country’s 82 provinces, the paper noted, and said the largest producers — including Nueva Ecija, Isabela, Cagayan, Iloilo, Leyte, North Cotabato, Pangasinan and provinces in Bicol — would be among the most affected if drones covered half the national rice area.

The paper warned that such displacement could destabilize rural economies, intensify migration pressures, and widen inequality.

Ecological risks tied to herbicide dependence

While Mendoza said precision spraying can reduce chemical waste and lessen farmer exposure to toxic substances, he cautioned that drone systems may also encourage heavier reliance on chemical inputs — especially herbicides.

The study cited common herbicides used in Philippine rice farming, including butachlor, pretilachlor, and pyrazosulfuron ethyl, and said these chemicals can disrupt soil microbial communities, reduce biodiversity and impair long-term soil fertility. The paper also raised the risk of chemical drift if drones are improperly calibrated, potentially affecting nearby ecosystems and communities.

A central concern in the assessment is that drone seeding supports direct-seeded rice systems, which the paper described as inherently more vulnerable to weeds than transplanted rice. In transplanted systems, established seedlings can outcompete weeds early. In direct seeding, rice and weeds emerge simultaneously, increasing competition and, the paper argued, heightening dependence on herbicides for weed management.

Over time, the paper said, continuous herbicide use can alter soil microbial community structure, reduce beneficial nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and contribute to declines in soil fertility.

‘Hidden costs’ from soil degradation

The assessment argued that short-term labor savings from drone seeding could be offset — or surpassed — by longer-term costs related to soil degradation and the higher input needs of degraded soils.

It cited restoration costs for rebuilding soil microbial diversity and organic matter through interventions such as biofertilizers, compost and green manures, placing the cost at P8,000 to P12,000 per hectare annually in cited studies. If half the national rice area — 2.4 million hectares — were drone-seeded and later required soil rehabilitation after prolonged herbicide dependence, the paper projected annual restoration costs of about P19.2 billion to P28.8 billion.

The assessment also said degraded soils can reduce water-holding capacity and nutrient cycling efficiency, increasing irrigation and fertilizer requirements. It cited an example in which transplanted systems typically require about 7,000 to 8,000 cubic meters of water per hectare per season, while direct-seeded systems in degraded soils may require 10% to 12% more water. Using an irrigation service fee of P0.50 to P1.00 per cubic meter, the paper estimated added water costs of P350 to P900 per hectare per season.

For fertilizer, the paper said transplanted systems with healthier soils typically apply 120 to 150 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare, costing about P6,000 to P7,500 per hectare. Degraded soils, it added, may require 20% to 30% more fertilizer, raising costs by an additional P1,200 to P3,000 per hectare. Scaled to 2.4 million hectares, the paper projected added fertilizer costs of about P2.8 billion to P7.2 billion annually and added water costs of about P840 million to P2.1 billion annually.

Taken together, the assessment placed the combined annual “hidden costs” of soil rehabilitation plus added fertilizer and water at about P22.84 billion to P38.1 billion under the 50% adoption scenario.

The paper described a feedback loop in which degraded soils require more synthetic fertilizers to sustain yields, which can further disrupt microbial diversity and soil structure, increasing dependence on external inputs and heightening environmental risks such as nutrient leaching and waterway contamination.

Financial barriers and inequality concerns

Mendoza’s assessment said the upfront cost of drone technology could reinforce unequal access.

It cited an approximate price of P1.7 million for a XAG drone and said that for smallholders the cost is prohibitive, making drone services more accessible through cooperatives or private providers. It cited average service fees of about P3,000 per hectare for drone seeding and about P1,500 to P2,000 per hectare for spraying.

While the paper said drones can reduce per-hectare input costs compared with traditional methods, it warned that high upfront investment and maintenance costs create financial risk — and that without subsidies or cooperative ownership, smallholders may be excluded from benefits and become dependent on service providers, undermining farmer empowerment.

Health trade-offs

On health impacts, the assessment said drone spraying can reduce farmers’ direct exposure to hazardous agrochemicals by limiting dermal contact and inhalation risks associated with manual spraying.

But it also warned that misuse or poor calibration can cause chemical drift, potentially exposing nearby communities, livestock and ecosystems. The paper said training for operators, adherence to recommended spray volumes, and stronger regulatory frameworks — including standards on buffer zones, permissible chemical loads and monitoring — are needed to safeguard health outcomes.

It also argued that integrating drones with Integrated Pest Management strategies could reduce overall chemical use while maintaining productivity.

Sustainability depends on how drones are used

The assessment said sustainability is not inherent to drone technology and depends on whether the program is embedded in inclusive policies and ecological farming practices.

If drones reinforce input-intensive farming marked by heavy herbicide and synthetic fertilizer use, the paper said they risk undermining long-term soil health, biodiversity and rural livelihoods. If paired with approaches such as Integrated Pest Management, organic inputs, soil health monitoring and cooperative ownership, the paper said drones could reduce waste, improve efficiency and support resilience.

Policy recommendations in the assessment

Mendoza’s paper recommended several safeguards:

- Retraining programs for displaced workers, including training in drone operation, maintenance, and ecological farming practices

- Cooperative ownership models to reduce costs and broaden access for smallholders

- Subsidies and credit access to support equitable adoption and prevent widening inequality

- Ecological integration, including Integrated Pest Management, organic inputs, and soil health monitoring to mitigate risks

- Regulation and training to ensure proper calibration and safe use, and to prevent chemical drift and misuse

- Employment safeguards, including social safety nets to cushion wage losses and stabilize rural economies

Bottom line

The paper concluded that Drones4Rice represents a significant technological advance that could modernize rice farming and deliver immediate efficiency gains through automated seeding, spraying, and fertilizer application.

But it warned that without safeguards, drone adoption could displace large numbers of rural workers, deepen dependence on chemical inputs, widen inequality, and degrade the ecological foundations of rice production — creating long-term costs that may outweigh short-term savings.