More groups ask SC to zap cybercrime law

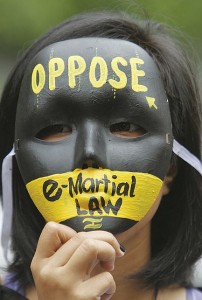

CYBER PEOPLE POWER A masked protester joins a big rally by different organizations composed of activists, journalists, netizens and bloggers in denouncing the online libel provision of the cybercrime law during a silent protest outside the Supreme Court on the eve of the law’s implementation. RAFFY LERMA

More groups have asked the Supreme Court to nullify the new Cybercrime Prevention Act.

Warning against what they described as “cyber authoritarianism,” the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, the Philippine Press Institute, the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, and individual journalists asked the tribunal to stop the government from implementing Republic Act No. 10175, which took effect Wednesday.

They also asked the court to hold oral arguments on the case and to stop the Department of Budget and Management from releasing the P50 million allocated for the law’s implementation.

“In this case of first impression, this court is asked to rule on a statute that, if allowed to stand, will set back decades of struggle against the darkness of ‘constitutional dictatorship’ and replace it with ‘cyber authoritarianism,’” said the media groups, which were represented by lawyers from the Free Legal Assistance Group.

“It is a law that unduly restricts the rights and freedoms of netizens and impacts adversely on an entire generation’s way of living, studying, understanding and relating,” they said.

This was the ninth petition against the cybercrime law. On Wednesday morning, members of the Ateneo Human Rights Center also asked the court to nullify provisions of the law for being unconstitutional.

OFWs, too

Overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) and migrants’ rights groups have joined protests against the new law, saying it will have an adverse effect on the freedom of speech and expression and access to information by 15 million OFWs.

“Social media, through social networking sites, help greatly in ‘connecting’ Filipinos abroad to the homeland and to other Filipino communities around the world because it is ‘real-time’ and accessible to them. Imposing e-martial law is tantamount to the curtailment of the access of information of overseas Filipinos,” said Connie Bragas-Regalado, president of Migrante Sectoral Partylist.

“More importantly, social media are also instrumental in aiding overseas Filipinos, especially migrant workers in distress, in bringing their plight and message to the public’s and the government’s attention,” Bragas-Regalado said.

Punishment without trial

In their petition, the media groups said the law should be scrapped for being a bill of attainder—or a legislative act that inflicts punishment without trial—and for violating the freedom of expression guaranteed by the 1987 Constitution.

They added that the law also violated the constitutional guarantee against double jeopardy or being charged twice for the same crime.

“In providing for a prosecution for cybercrime ‘without prejudice to any liability for any violation’ of the Revised Penal Code or special laws, Sections 7 and 6 (of the new law) violate the prohibition against double jeopardy,” the media groups said.

They said the cybercrime law also violated constitutional provisions on due process and equal protection under the law.

“The blanket increase of penalties across the board by one degree for all felonies and crimes under Section 6 (of the new law), regardless of the nature of the felony or crime and regardless of their relation to the public policy set forth in Section 2, discriminates against those who use ICT (information and communications technology),” the media groups said.

Take down provision

The petitioners also scored the law’s “undue delegation of judicial powers” to the secretary of justice, the Philippine National Police, and the National Bureau of Investigation.

They cited in particular the provision giving the secretary of justice the power to “take down” online content deemed to be in violation of the law.

“The ‘take down’ clause under Section 19 violates due process as well as equal protection. Not only does it allow the secretary of justice to seize property without due process, it also allows an executive determination of what should be a judicial finding and, then, on an extremely low standard,” the media groups said.

“Effectively, the secretary of justice is a one-person tribunal, anathematic to the constitutional guarantee of due process and every notion of fundamental fairness,” they added.

The petitioners said the power to “restrict or block access to computer data” amounted to a seizure of property, which is reserved for a judge under the Constitution.

“Notably, it is also a power that can only be exercised after the issuance of a warrant,” they added.

The petitioners alleged that the law violated the right to privacy of communication and correspondence as “it allows the real-time collection of (online) traffic data and effectively surveillance without a warrant.” With a report from Tina G. Santos