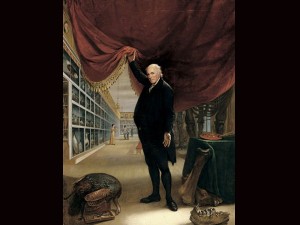

Charles Willson Peale pulling back a curtain to reveal the scientific and artistic wonders held at his museum to spark a visitor’s curiosity. Peale’s self-portrait is on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's exhibit, “Great Hall of American Wonders,” which explores 19th-century innovations through art in the landmark Washington building once known as the “temple of invention.” (AP Photo)

WASHINGTON — The Washington building known as the “temple of invention” when it was built in 1836 to hold the nation’s patents is revisiting its roots, hosting a new “Great Hall of American Wonders” to explore 19th-century innovations through art.

The idea for this major exhibit that opened Friday at the Smithsonian American Art Museum was sparked in part by talk among experts that the United States is losing its edge in innovation as other countries spend more on research and export more technology and foreign companies gain more U.S. patents. Curators pulled together artworks, inventions and scientific discoveries from the 1800s in an unusual project for the museum to show how Americans came to believe they have a “special genius” for invention.

Guest curator Claire Perry said the early decades of the 19th century were a time of crisis as the nation’s last founding fathers died, causing worries the country might not survive. Perry, who specializes in 19th-century culture, previously was a curator at Stanford University.

“The new generation was terrified they might fail,” she said. “But they were energized by their shared belief in American ingenuity, by the idea that the people of the United States were natural-born problem solvers.”

During this time, the nation’s inventions were put on display to be celebrated. Some 100,000 people each year visited the old patent office building in downtown Washington to marvel at Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, Cyrus McCormick’s grain-harvesting reaper and Samuel Morse’s telegraph, among many other inventions by average citizens.

Now part of the Smithsonian, the building once again is displaying patent models from the 1800s. They include designs for a machine to make paper bags, a sewing machine, a locomotive and handgun prototypes in the exhibit organized with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which is now based in Alexandria, Virginia.

Perry said she drew inspiration from Charles Willson Peale, a painter and naturalist from Maryland who founded one of the first museums in Philadelphia, because he insisted that invention, not the revolutionary generation, was the key to building the nation.

A primary image of the exhibit is Peale’s self-portrait, “The Artist in His Museum,” showing him pulling back a curtain to reveal the scientific and artistic wonders held at his museum to spark a visitor’s curiosity.

The exhibit retraces such inventions as the first mass-produced American clock, the gun and the railroad with patent models, diagrams and drawings. There are paintings by such artists as Thomas Eakins, Thomas Moran and Morse, the telegraph inventor.

“The mash up of art, science and technology in the exhibition is about breaking down traditional boundaries that block our inventive juices,” Perry said. “In this time where people are sort of wondering about what we are, we’re still inventors, but we need to frame our own perceptions in that way.”

Perry said the nation’s inventive spirit has been forgotten somewhat as other countries have challenged U.S. dominance. Many point to declines in U.S. education in the arts, science and math, compared to global competitors, and the White House has called for a reinvestment in training for such creative disciplines.

Among the 162 objects on display is the golden cast of the final spike that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. There is also a drawing for President Abraham Lincoln’s patent application for a device that could buoy steamboat vessels stuck in shallow water. Other sections examine technology’s impact on natural resources, such as the once-vast buffalo herds.

Museum Director Elizabeth Broun said it’s rare to pull so many historical works and three-dimensional objects together in a place where they were once held up as examples of the nation’s progress.

“Each one in itself is a story, a treasure, that has a background that helps flesh out a piece of the puzzle,” she said.