Robotic device winds its own way through beating pig heart

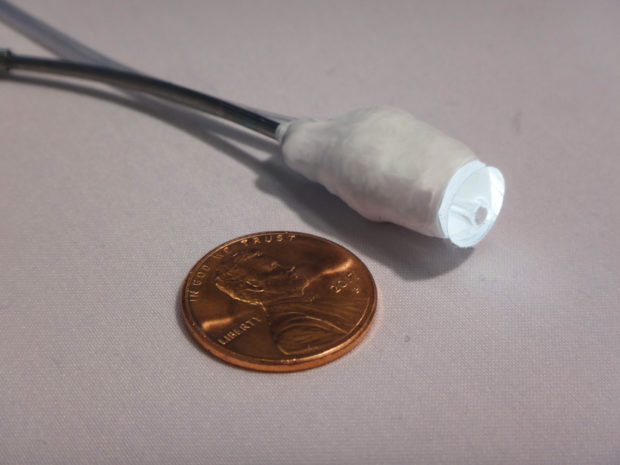

This undated photo provided by Margherita Mencattelli in April 2019 shows the tip of a robotic catheter equipped with a small camera and lighting encased in silicone, in Boston. Described in a report released on Wednesday, April 24, 2019, the device guided itself through the delicate chambers of a pig’s heart as it was beating. AP

WASHINGTON — Borrowing from the way cockroaches skitter along walls, scientists have created a robotic device that safely guides itself through the delicate chambers of a pig’s heart as it’s beating.

It is one of the first times researchers have shown that a truly autonomous surgical robot can navigate inside the heart, not controlled by a doctor with a joystick, according to a study in Wednesday’s journal Science Robotics .

Heart surgeons routinely push a thin tube called a catheter through twisting and turning blood vessels to make repairs in the heart without open surgery. But how does a robotic version find its own way through moving heart tissue and with blood swishing in the way?

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital turned the catheter’s camera tip into essentially an “optical whisker,” said cardiac bioengineering chief Pierre Dupont, the lead researcher. Just as cockroaches navigate along walls and rats reach out with their whiskers, the catheter maps its path through the heart, tapping periodically against the heart’s valve and wall ever so lightly — with about the force of a stick of butter sitting in your hand, Dupont said. The technology combines the camera’s images with machine learning to interpret what tissue it’s touching and how hard.

“This robot is trying to walk along the wall of the heart until it gets to the valve,” Dr. Uma Duvvuri of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who heads a robotic innovation lab but wasn’t part of Wednesday’s study. “That’s a pretty exciting development but this is still very, very preliminary.”

If your heart has an irregular rhythm — whether constantly or occasionally — you should make an appointment with your primary care doctor or a cardiologist. https://t.co/vtEuA4KBdT pic.twitter.com/jFQfPyKXju

— UPMC (@UPMCnews) April 24, 2019

The demonstration technology is still years away from any operating room, and isn’t designed to replace a surgeon, Dupont said. Instead, he said it might free up a surgeon’s time to focus on harder tasks, comparing it to a plane’s autopilot — and also reduce the time patients and medical staff are exposed to X-rays that currently are needed for navigation.

“The easiest part of autonomy in surgery is the technology,” Dupont said. “The hardest parts are the politics, the regulatory” approval and legal efforts.

Dupont’s team tested the robotic catheter in 83 procedures in live pigs in a lab. The device found its target, on average taking seconds longer than a doctor threading a catheter into place. But Dupont said the robotic catheter will learn, just like humans, and get better and faster with more practice.

Russ Taylor, a medical robotics specialist at Johns Hopkins University, called the technology clever and the study “a significant achievement, but I wouldn’t flag it as a breakthrough.”

Robots with different levels of autonomy have been used in surgery for radiation therapy and orthopedics, said Taylor, who wasn’t part of the research. And Pittsburgh’s Duvvuri pointed to studies with a robot that can stitch tissues together without human help.

Still, true autonomy, “in my humble opinion, it’s still a hammer looking for a nail,” said Duvvuri, who couldn’t think of an area where it would improve a procedure.

And while the new study focused on a potential heart use, Duvvuri said adding that sensing technology to catheters could have other uses, such as helping to diagnose risky growths in the colon.

Added Hopkins’ Taylor, “I see things evolving where the machine keeps undertaking more and more discrete tasks while working in partnership with the humans.”