Why anyone could potentially fall for a conspiracy theory

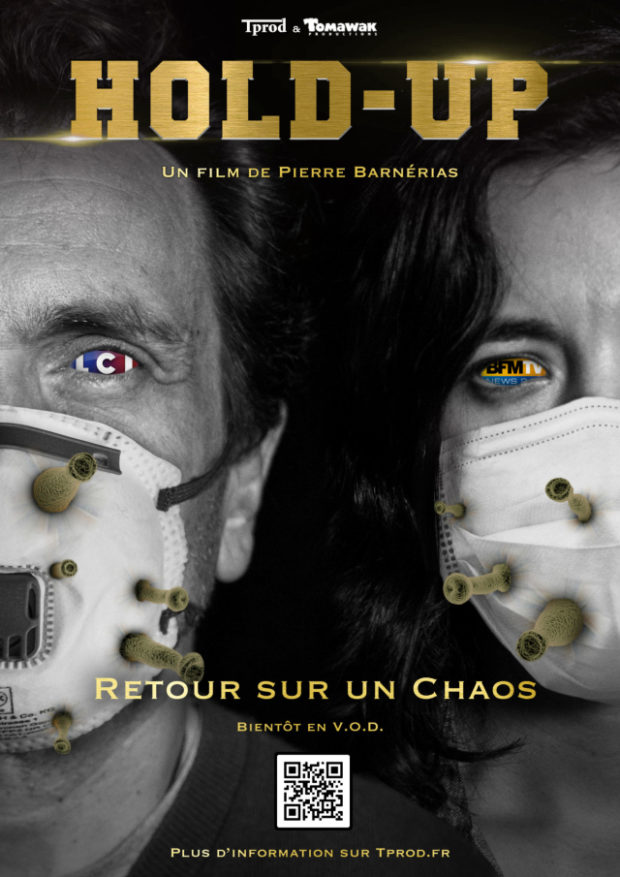

Conspiracy theories have been rife since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, as seen with the success of the French documentary “Hold-Up” by Pierre Barnérias. Image: Tprod and Tomawak via AFP Relaxnews.

Is it all a complete fabrication by the powers that be? Are our leaders complicit in a forced vaccination program? Conspiracy theories have been rife since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The “Plandemic” videos that went viral earlier this year and the recent success of controversial French documentary “Hold-Up” by Pierre Barnérias, released on Nov. 11 and which features several debunked conspiracy theories, are proof enough of that.

This climate is fostered by the many unknowns and uncertainties surrounding this unprecedented global health crisis, explained the psychologist Albert Moukheiber, who also holds a doctorate in neuroscience.

What’s going on in someone’s mind when they buy into a conspiracy theory?

Albert Moukheiber, Ph.D.: When an individual believes a conspiracy theory, by definition, they don’t know that it’s a conspiracy. We all try to create a coherent picture from very patchy information, whether it’s about a virus, unemployment or politics… So, the individual who buys into a conspiracy theory thinks that they are in the process of understanding what’s going on, because they are being given a proposed explanation.

This is borne out even more when such theories are based on uncertainty. When faced with an unknown situation, we will be more likely to opt for the story that suits us. It’s a bit like horoscopes, in the end: they’re written in an ambiguous way so that everyone can identify with them at a given time.

A new virus that strikes the whole world — that’s something completely unprecedented! For example, I don’t think that many people see car seatbelts as a restriction of their freedom. The difference between seatbelts and [face] masks, is that seatbelts have been established or accepted for a long time, whereas masks are new and have been subject to many contradictions.

The phenomenon is nothing new, but it’s largely amplified by social media. At the time when HIV came to light, there were many delusions about the virus, but the speed with which information spread wasn’t the same at all.

To what extent can fear feed these delusions?

Fear is an emotion like any other, and I don’t know why it’s given such great importance compared to other emotions. Fear doesn’t belong to any specific camp: it can sometimes be legitimate, sometimes exploited.

If we look at the public health crisis situation with a little perspective, we realize that, in less than a year, we have established the nature of the virus, put in place public policies to try to eradicate it, developed tests, etc. And yet, some will claim that we’re being lied to as a way of better controlling us, and so there’s no reason to be scared of the virus. Conversely, those who don’t buy into those theories encourage being scared, both to protect themselves from the virus and from these conspiracy theories.

In the case of conspiracy theorists, I also think that it’s more “reassuring” to clearly identify one (or several) things that are responsible for this crisis. To interpret the facts, some may prefer to look to humans rather than to a complex and systemic cause (simultaneously environmental, political and economic).

In the end, anyone could potentially be susceptible to falling into the trap. How can we protect ourselves against that?

I think that it’s both a question of confidence, wariness and information. And also suspicion when faced with someone offering a story that will be “convenient” for us. When seeking to create a shared reality, you need to try to reason in terms of percentages. That’s why, in the field of science, we don’t publish our research in a documentary or a film, because we get it checked by peers. Does that make us infallible experts? Absolutely not! Scientific methodology is about research, but it’s also about having safeguards in place to reduce the margins of error.

In fact, I think the principle should be the same everywhere, particularly in the media. I’ve always been surprised by certain TV commentators who monopolize air time in shows, giving their opinions on subjects (politics, sport, the economy, etc.) when they aren’t experts in those fields!

But people have got used to that being acceptable, even well before the “Hold-Up” film. So, to say that people who believe conspiracy theories are just “stupid” to me seems unfair and incorrect, insofar as that mostly amounts to criticizing an infotainment culture in place for 15-20 years, and which, I believe, has nothing to do with intelligence. CC

RELATED STORIES:

Facebook, Instagram ban QAnon conspiracy linked accounts

Some Indonesians still believe COVID-19 a conspiracy — survey