Filipino scientist helps make cooking on Mars possible

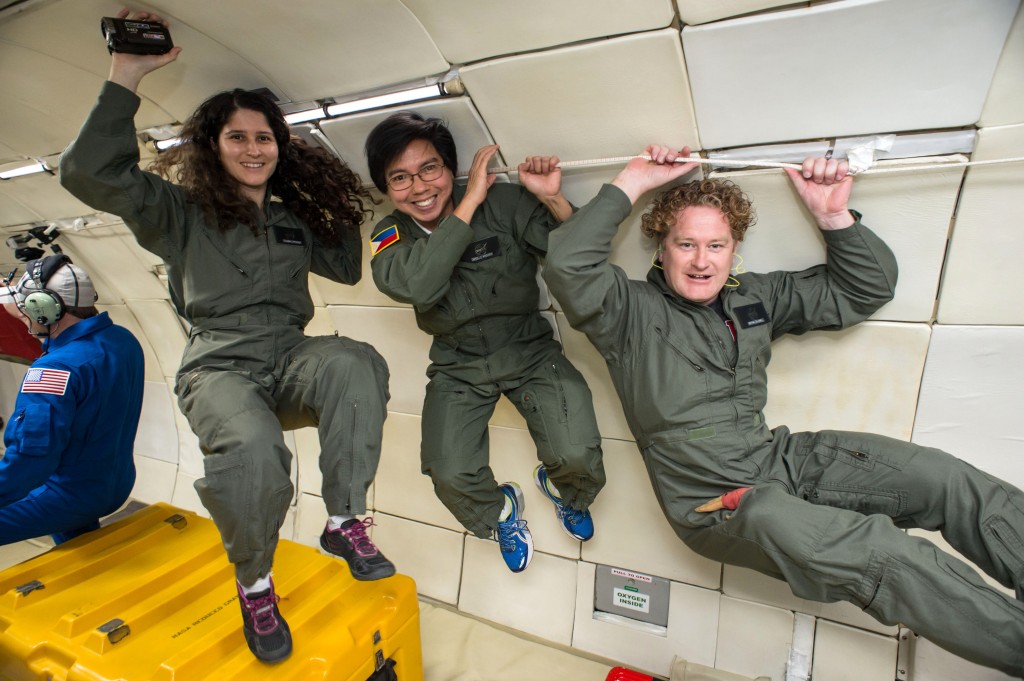

Apollo Arquiza (center), with Bryan Caldwell (right) and Susana Carranza, aboard the G-1 Force space simulator aircraft. NASA PHOTO

- Cornell team develops device for cooking in zero gravity

- UP Los Banos scientist is in postdoctoral program that made it

NEW YORK—For the next NASA space explorations, astronauts would soon be able to cook as if they were in their own home kitchen, without worrying about their ingredients floating away when they stir-fry in a zero gravity spacecraft, thanks in part to a Filipino scientist.

According to Apollo Arquiza, a postdoctoral research associate at Cornell University, it is now possible to cook on the moon or Mars without having the shredded potatoes and sizzling oil travel a greater distance from the pan.

Does it seem like a scene from a George Clooney movie? Yes. But can it really be done with modern-day technology and applied research? Absolutely.

“Even daing [dried fish] can now be fried, if there’s a Filipino aboard the spacecraft,” Arquiza, 45, said in an exclusive phone interview with INQUIRER.net. “No one in the world has ever done anything like this before.”

Arquiza was part of the team that designed the first low-gravity space galley ever recorded in history.

After a series of rigorous research and testing that started since 2011, the team led by Jean Hunter, assistant professor and director of undergraduate programs at Cornell’s College of Biological and Environmental Engineering unveiled the result early this year: a prototype cooking device which, to the untrained eye, may just look like an ordinary oven enclosed in a giant stainless metal box.

Last April, the team boarded a G-Force 1 space simulator aircraft to test the effectiveness of the galley. In a series of four flights from Houston, they sautéed tofu and potatoes in a frying pan.

Although the experiment was described as “a bit messy,” with oil splatters floating away, Arquiza said the results were crucial steps to improving the design of future terrestrial and extraterrestrial cooking technology.

“Gravity on Mars is only one-third as that on Earth,” he said. “The biggest challenge here is how to control the oil splatter from traveling.” Under low-gravity, he added, oil droplets are much bigger, more numerous and do travel more.

Mission to Mars in 2030

How significant is this new cooking innovation for space missions?

The U.S. government has reportedly been working on a NASA-led manned mission to Mars in 2030. With plans of establishing a permanent base on the Red Planet, Arquiza says, astronauts may have to stay there for a year or longer.

Traveling alone from Earth to Mars could take up six to eight months, depending on planetary alignments. That means that astronauts need to have the right amount of food for the entire duration of their mission.

“If they [astronauts] eat the same food over and over again, they could experience some kind of food fatigue,” he said. “So, if they are going to be on Mars for a long time, they may have to cook at some point.”

Astronauts today eat pre-packaged and freeze-dried meals that they get from the International Space Station. Yet experts are concerned that such diet has inadequate nutrition, making them malnourished, and that it may be difficult on their minds and bodies to sustain longer space visits.

From Los Baños, Laguna to Ithaca, NY

Before he came to Cornell University, an Ivy League school located in Ithaca, New York, to earn his doctoral degree in biological and environmental engineering, Arquiza was an adjunct professor at the University of the Philippines-Los Baños (UPLB) College of Engineering.

“My goal at the time was just to earn my PhD,” he said, “and, hopefully, get tenured and have a guaranteed permanent teaching position at UPLB.”

But during the course of his studies, he said, Professor Hunter became his academic adviser, and she then asked him to be part of the Reduced Gravity Program team, including another Cornell University research associate, Bryan Caldwell, and Susana Carranza, a scientist engineer from Makel Engineering in Chico, California.

“Getting accepted into Cornell’s PhD program is already a huge opportunity for me. Everything is free, and I get a monthly allowance,” Arquiza said. “But to be part of the team was a much bigger opportunity. I just feel very lucky.”

In most premier US universities, where there is a higher endowment to cover financial costs for doctoral and postdoctoral programs, admitted students are offered free tuition fees and living allowances.

Named by his parents after Apollo 11, the spaceship that NASA launched to the moon in 1969, the year he was born, Arquiza feels at times that “everything seems coincidental.”

Nevertheless, each time he gets introduced in relation to his research on low-gravity cooking, he says that people would give him a smile, alluding that his name is meant for his job.

“Nakakatuwa din [It’s quite amusing],” he said.

Back to the future

While there could be more future opportunities that await him in the United States, Arquiza admits that staying or going back to the Philippines after he finishes his postdoctoral work is “a hard decision to make.”

Considering the resources of the Philippine government for science and research, he is aware that a landmark project, like the one that he has been currently involved in, might not be available.

“Perhaps, if I decide to continue working in the US, it would be a short-term consulting work,” he noted. “I can’t just tell, for now. Pero hindi rin siguro ako magtatagal [But I guess I won’t stay that long].”

Arquiza is committed to giving back to his country. The Philippine government, he says, paid almost his entire academic life, from his years at the Philippine Science High School to UP-Los Baños as a recipient of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) scholarship program.

“I owe our country a lot. I have already gained here [United States] the research expertise I needed, so I can teach again and share that with fellow Filipinos,” he said. “I can use my training and expertise on food security and food processing.”

Since he started his doctoral program seven years ago, Arquiza has not had a chance to go back to the Philippines. He said that his wife, Amy, who is also teaching at UPLB, had visited him a few times, and that they were able to spend time together and see some tourist-spots in New York City.

“Some of the people I know back home, when I told them that Cornell is in New York, they immediately think of New York City,” he said. “It’s funny because they are surprised when I told them, ‘No, I’m in a rural area.’”

Still, for Arquiza, being away from his native Laguna province seems like a million light years away from home. “Yes, I miss my family,” he said.