Ebola may persist in semen for 9 months—study

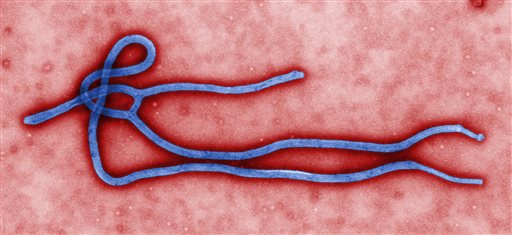

This undated file image made available by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) shows the Ebola virus. AP

MIAMI, United States—The Ebola virus may persist in some men’s semen for nine months after they were initially infected, far longer than previously thought, according to preliminary research out Wednesday.

READ: Ebola: Simple methods of protection

The first long-term study of its kind, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, adds to growing evidence that Ebola can linger in the body, causing health problems for months or even years.

The findings raise new health concerns for the survivors of the Ebola epidemic that has ravaged West Africa since late 2013, killing more than 11,000 people in the deadliest outbreak since the virus was first identified in 1976.

“These results come at a critically important time, reminding us that while Ebola case numbers continue to plummet, Ebola survivors and their families continue to struggle with the effects of the disease,” said Bruce Aylward, the World Health Organization’s special representative on the Ebola response.

“This study provides further evidence that survivors need continued, substantial support for the next six to 12 months to meet these challenges and to ensure their partners are not exposed to potential virus.”

READ: Ebola: How it spreads

In March, researchers published a study describing the case of a Liberian woman infected with Ebola through sex with a survivor—six months after his infection was diagnosed.

“Before this case, the furthest into convalescence that Ebola virus had been isolated from semen was 82 days,” said Armand Sprecher, an Ebola expert with Doctors Without Borders.

The first known case of sexual transmission of a virus within the Ebola family was documented in 1967 when a woman was infected with Marburg virus through sex with her husband, six weeks after he recovered, Sprecher added.

Research findings

A total of 93 men from Sierra Leone enrolled in the study to examine semen samples for the presence of Ebola virus genetic material.

The men joined the study between two and 10 months after they were infected with Ebola.

All those who were tested in the first three months after their illness showed positive results for Ebola in the semen.

Four to six months after diagnosis, 65 percent were positive.

About a quarter (26 percent) of those tested between seven and nine months were positive.

It remains unclear why some men retained fragments of Ebola virus and others did not.

Researchers are also unsure whether these trace levels could mean the men were still infectious to partners.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is conducting further tests to determine if the samples contained live, potentially infectious virus.

Survivors struggle

There are more than 8,000 male survivors of Ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, and experts are urging them to use condoms until their semen has twice tested negative for Ebola.

People who survive Ebola are considered cured once the virus is no longer detectable in the bloodstream, typically within weeks of infection.

An outbreak of Ebola in a given location can be declared over 42 days after the resolution of the last case, according to the World Health Organization.

But many experts now think that a period of increased surveillance and caution should extend to 90 days, or even longer.

“This is a highly important paper,” said Susan McLellan, clinical associate professor of Tropical Medicine at Tulane University.

“It was known to some extent that the virus could persist in semen for a long time after it cleared from blood but we really didn’t know how long.”

The latest study was released just as a British nurse fell critically ill due to a resurgence of the Ebola virus, following her successful treatment in January.

“This virus is incredibly adept at hiding in places in our bodies considered immune privileged sites, places where we don’t have a lot of surveillance by the immune system, such as the eyes and the testes,” said Ilhem Messaoudi, associate professor of biomedical sciences at the University of California, Riverside.

“So even if you don’t have the virus in your bloodstream it can be hiding out in these immune privileged sites and we need to be aware of that because it’s setting the stage for potentially new outbreaks.”