Freud and the Nobel trauma

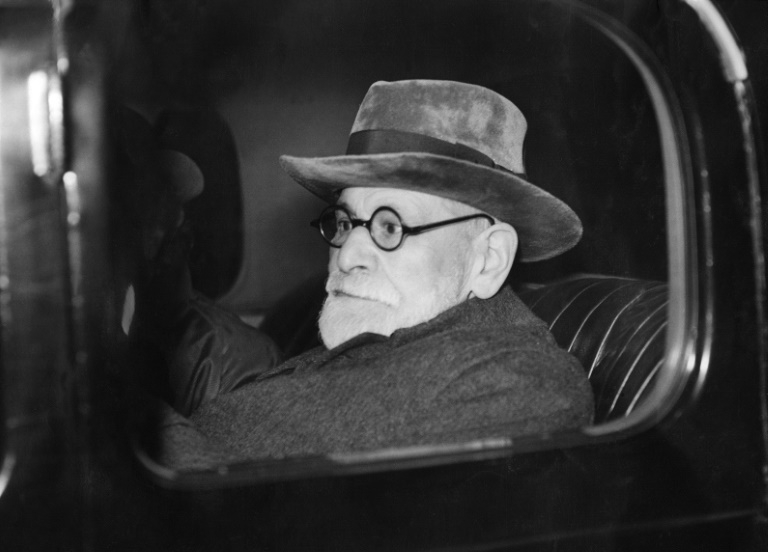

Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, seen here in London in 1938, knew he would never be awarded a Nobel science prize. Image: Planet News/AFP

Sigmund Freud, a man of letters or the mind? Neither, according to the Nobel committees, which not only gave the father of psychoanalysis the cold shoulder but even criticized his work.

Nominated for the Nobel Medicine Prize for the first time in 1915 by United States neurologist William Alanson White, Freud went on to be nominated for a Nobel a total of 13 times until 1938, one year before his death in London.

Freud’s name was put forward 12 times for a Medicine Prize and once for a Literature Prize.

In 1937, no fewer than 14 prominent scientists, including several Nobel laureates, backed the nomination of the Austrian doctor, who liked to compare himself to Copernicus and Darwin.

But their support was in vain.

Very early on, Freud “understood that he could never win a Nobel science prize. Psychoanalysis was already under attack as not being a science. He was hurt,” Elisabeth Roudinesco, the author of the biography “Freud, In his Time and Ours”, told AFP.

In 1929, professor Henry Marcus of the Karolinska Institute, home to the Nobel medicine committee, cruelly summed up the scientific community’s mistrust of Freud’s doctrine:

“Freud’s entire psychoanalytic theory, as it appears to us today, is largely based on a hypothesis,” with no scientific proof that a neurosis can be traced back to the existence of a childhood sexual trauma—if a trauma even existed, he wrote in a document unearthed by Swedish academic Nils Wiklund in 2006.

Roudinesco agreed: “His critics were right about the Oedipus complex, because he had become dogmatic about that.”

But one cannot write off Freud’s entire body of work, she said, noting his important contributions to the study of the soul.

Before Freud, “all psychiatrists regarded the hysterical woman as a madwoman, the masturbating child as a pervert and the homosexual as a degenerate,” she said.

“Very good literary style”

Faced with the Nobel science committees’ lack of interest in him, Freud’s close friend and translator Princess Marie Bonaparte of France tried to round up support for a Nobel Literature Prize instead, when he was in his 70s and was suffering from jaw cancer.

Romain Rolland, the French novelist who won the Nobel Literature Prize in 1915, was well-placed to nominate Freud, with whom he had corresponded but who had not written a single line of fiction.

On January 20, 1936, Rolland wrote to the Swedish Academy to propose Freud’s name.

In the letter, which is kept in the Academy’s archives, Roland sought to pre-empt any prejudice its members may have against Freud.

“I know that at first glance the illustrious scientist may seem more suited for a medicine prize,” he wrote. “But his great works… have paved the way for a new analysis of emotional and intellectual life; and, in the past 30 years, literature has been profoundly influenced.”

Rolland neglected to mention that Freud had won the prestigious Goethe Prize in 1930.

Per Hallstrom, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy at the time, did not mince his words about Freud’s nomination:

“When it comes to the presentation of his theories, it is easy to note the acuity, the fluidity and the clarity of his dialectic. He unquestionably also has a very good and natural literary style,” he wrote, before adding hastily: “Apart perhaps from the actual ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ on which his entire doctrine is based.”

Freud, he concluded, “should not be awarded any poet laurels, no matter how poetic he has been as a scientist.”

End of discussion.

No endorsement from Einstein

Eighty years later, Odd Zsiedrich, the Academy’s administrative director, is a bit more diplomatic. “The competition was very stiff” in 1936, he said of a year in which American playwright Eugene O’Neill got the nod.

Albert Einstein, who won the Physics Prize in 1921, refused to endorse Freud’s nomination for the Medicine Prize in 1928.

“About the truth content of Freud’s teachings, I cannot come to a conviction for myself, much less make a judgement that would be an authorisation to others,” Einstein wrote, according to historian John Forrester.

Five years later, Einstein and Freud went on to publish “Why War?” a series of letters between them discussing peace, violence and human nature.

In May 1939, after reading Freud’s last book “Moses and Monotheism”, the man behind the theory of relativity gave him an ambiguous compliment: “I quite especially admire your achievements, as I do with all your writings,” he wrote before adding: “From the literary point of view.” JB

RELATED STORY: