Japan debates how much to regulate genetically modified food

TOKYO — An expert panel of the Environment Ministry started discussions Tuesday on issues related to genome editing technology, including the range of regulations that should apply to its use in food.

Genome editing technology allows genes to be modified for a particular purpose. In Japan, it is currently being used in the development of farm products and animals, including tomatoes rich in a substance that restricts increases in blood pressure and madai red sea bream with increased muscle mass.

The panel members will discuss various issues, such as information control regarding the distribution of such products.

A genome contains all the genetic information about a living organism and is composed of a sequence of four types of bases inside the DNA of cells.

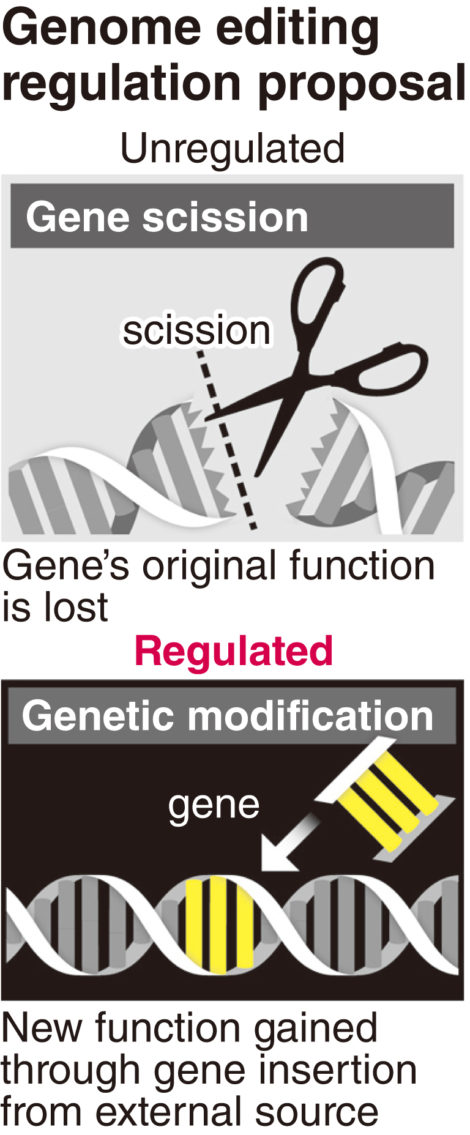

Genome editing technology can produce a genetically modified organism (GMO) by inserting a useful gene into the organism from an external source. It is also used for efficient breed improvement by scissioning an existing gene, so it will not function.

This scission technique is used in genome-edited living organisms developed in Japan. For example, the sea breams with greater muscle mass are produced by cutting out a gene that restricts muscle increase.

Production of a genetically modified organism is regulated by the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, based on an international framework. People who wish to grow such crops, for example, must receive approval from the government.

The panel will focus on the handling of genome-edited organisms produced with this gene scission technique. When this technique is used on an organism, it becomes impossible to tell whether the gene has been eliminated artificially or naturally, even when the organism’s genes are examined.

At the meeting, the ministry will propose that such cases should be exempt from regulation by the protocol, and discuss the pros and cons of a system to track the information.

The Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry, which manages food safety, is also planning to devise a legal framework by the end of fiscal 2018.

While Japan is accelerating discussion on the use of the technology, opinions are divided overseas. The U.S. Agriculture Department’s policy is to not regulate genome edited crops that have not been modified with a gene from an external source. In Europe, where consumers are strongly opposed to genetically modified food, the European Court of Justice said in a July 25 statement that such organisms “are, in principle, subject to the obligations laid down by the GMO Directive.”

“Safety and people’s peace of mind are essential to the spread [of genome edited products],” said a committee member of the meeting.

“Even when it’s decided that [some organisms] are exempt from the regulations, it’s important that each ministry and agency concerned should gather information and create a system for information disclosure,” said Nagoya University Prof. Masashi Tachikawa, who is knowledgeable about the relationship between genome editing and society.

Lingering concerns

Consumers’ concerns are the main worry in putting the technology to practical use. Farming of genetically engineered crops produced by technology other than genome editing became common practice overseas more than 20 years ago. In Japan, however, commercial farming of such products never took off, due to strong concerns among consumers.

According to the Council for Biotechnology Information Japan, pest-resistant corn, herbicide-resistant soybeans and other genetically modified crops were grown in 24 countries, including the United States, in 2017. Japan imported an estimated 20 million tons of such products yearly for cattle feed and edible oils.

There have been no reports of harm to people’s health from such genetically modified crops, but a survey by the Cabinet Office’s Food Safety Commission in fiscal 2016 found 35 percent of respondents were concerned about the safety of such products as food.

A consumer survey by Hokkaido University, on the other hand, found a tendency for people to accept some generically modified crops and genome-edited crops, such as sweeter melons and tomatoes as well as buckwheat devoid of allergens.

“Even if consumers may think genetic modification is not dangerous, they have a vague uneasiness. I think they have the same kind of concern about genome editing as well,” consumer life adviser Emi Gamo said. “For genome-edited crops to be accepted, it’s important to show consumers their actual merit.”